The Open Global Glacier Model¶

The Open Global Glacier Model (OGGM) is an open source modelling framework for glaciers. It has been developed since 2014: intermittently at first, and more regularly since 2016. Today, OGGM is continuously discussed and updated by a team of researchers in various institutions.

“OGGM e.V” is a registered non-profit organization, which purpose is the promotion of science and research in the fields of climate and glaciology; it does so by coordinating the development of OGGM and OGGM-Edu, and by organizing events around the topic of large-scale glaciology.

Website: https://oggm.org

Model documentation: http://docs.oggm.org

Online tutorials: http://oggm.org/tutorials

Source code: https://github.com/OGGM/oggm

Social media (twitter): https://twitter.com/OGGM_org

Anyone can participate in the development of OGGM. In practice, however, the main bulk of development and funding effort in the past have come from the Universities of Bremen (Ben Marzeion) and Innsbruck (myself). I have contributed to the vast majority of the codebase, while strategic decisions have been shared between Ben and me, and in recent years with a growing community of users.

This chapter briefly describes the OGGM project, its mission and building blocks. It concludes with a discussion about some of the challenges the project is facing. For a discussion about the project’s future and long-term perspectives, refer to chapter 07.

Objectives of the OGGM project¶

The main mission of the OGGM project is to:

Develop a global scale, modular, and open source numerical model framework for consistently simulating past and future global scale glacier change

Global scale means that OGGM should be applicable to all the world glaciers. This also means that it should be applicable to a smaller ensemble of glaciers, for example at the catchment scale, or even one single glacier. However, OGGM’s main added value will always be its ease of use and applicability to large numbers: this means that it is acceptable for us that OGGM is less useful or accurate at the single glacier scale than other methods would.

Modular means that we want OGGM to allow for different modelling approaches, for example different representations of ice flow or of the surface mass balance. Although we have to pick a default modelling workflow for the model to work “out of the box”, we do not want to enforce it. This has long been misunderstood outside the OGGM community, and in recent years we have put more effort in re-branding OGGM as a “modelling framework” rather than a model alone. The importance of modularity for running model intercomparison experiments is discussed below.

Open source means that code can be read and used by anyone so that new modules can be added and discussed by the community. OGGM’s permissive license allows any individual or entity to use it without any restriction. It also means that we will always put a lot of effort on code documentation and testing: indeed, very much like data without metadata, code without a documentation is practically useless.

Consistency relates to all three points raised above. Consistency in the modelling chain (regardless of the glacier or region it is applied to) allows providing uncertainty measures at all realizable scales (in theory - in practice this is quite complex). Consistency combined with modularity allows running sensitivity experiments with fixed and well controlled boundary conditions: it allows isolating specifically for the influence of a parameterization choice rather than a suite of modelling decisions. Consistency in the context of open-source development means that a fixed OGGM version should always produce the same results, regardless of the computer and operating system that was used to run it. It also means that differences between OGGM versions should be documented and that older OGGM versions should be permanently archived.

Project non-goals¶

Our project does not aim to make of OGGM the single venue for future regional or global glaciological studies. We strongly believe in the usefulness of model inter-comparisons and on the necessity to have various ways to solve the same problem, for the sake of scientific repeatability and replicability. “Healthy” competition drives innovation.

However, we attempt to encourage model developers to make their model operable within the OGGM workflow, while still keeping their model’s specificities, name, code, etc. under their full control and outside the OGGM namespace. We believe that this will greatly facilitate the standardization and execution of future model inter-comparisons.

Fundamental concepts¶

I briefly summarize the model’s building blocks: not to be comprehensive, but to give enough of an overview for the readers to understand the discussions that will follow. For a more in-depth introduction, refer to the GMD paper or the model documentation.

Glacier centric model¶

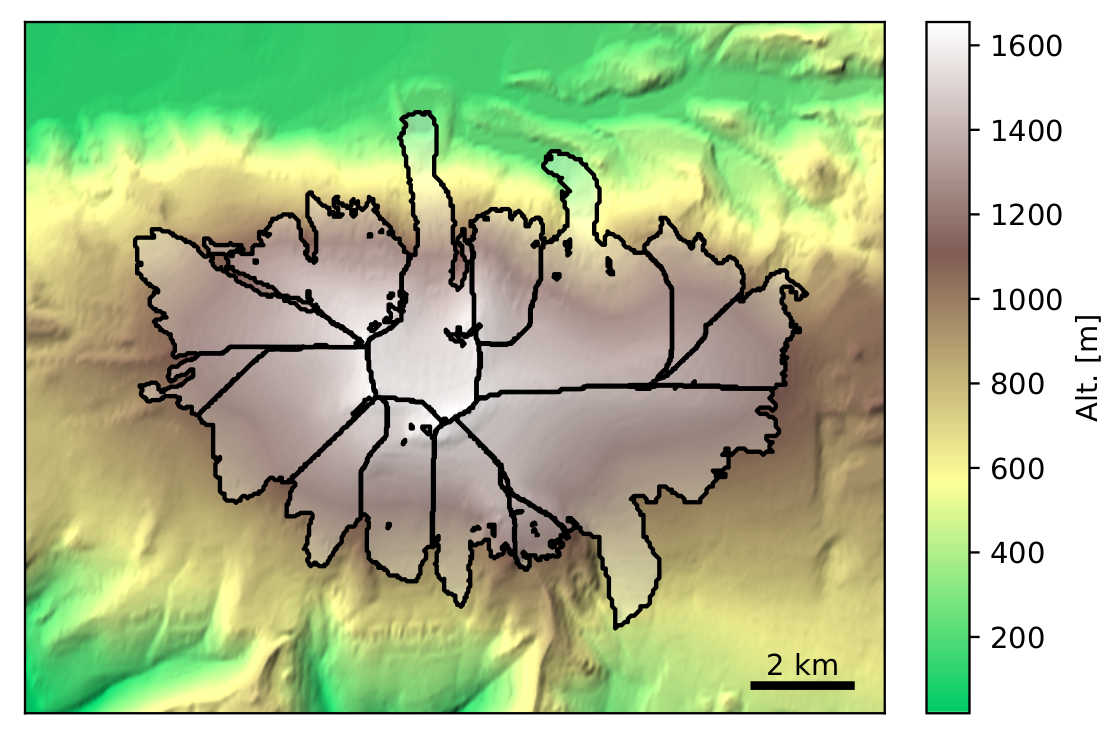

OGGM is what we called a “glacier centric model”, which means that it runs for each glacier independently of the others. In the case of glacier complexes, it relies on the glacier inventory to properly separate the individual glacier entities by the ice divides, ensuring that all ice in a glacier basin flows towards a single glacier terminus (this is unfortunately not always the case).

Fig. 1 Glacier centric approach applied to the Eyjafjallajökull ice cap in Iceland.

Glacier outlines provided by the Randolph Glacier Inventory v6.0.¶

The glacier centric approach is used by most large-scale glacier models to date. Alternative strategies include global gridded approaches [35], where all glaciers in a model grid cell are added together and possibly organized into elevation bins. Another approach is to handle entire glacier complexes as one single body of ice (“ice caps”). This is physically consistent and feasible, but requires either distributed models of ice flow [42] (computationally expensive) or implies simplifications to the glacier geometry (so that all ice flows downwards, [24]).

The advantage of glacier centric models is their adherence to the de-facto standard inventory of glacier outlines: the Randolph Glacier Inventory. Any glacier can be selected and simulated, and the model output can be compared to standard reference datasets such as length changes or surface mass balance data from the World Glacier Monitoring Service. Various models can be compared on a glacier per glacier basis or a combination of them. It is also computationally efficient, since models can focus on simulating the areas where glaciers are really located. This may sound trivial, but glacier centric models can also make use of the glacier location as a boundary condition, e.g. by excluding unrealistic solutions to the problem of computing mass balance or inferring ice thickness, for example.

The disadvantage of glacier centric models is their questionable scientific validity in presence of glacier complexes and ice divides (this problem can be mitigated by defining glacier complexes as one single entity, requiring other strategies than currently standard in OGGM). A larger issue of glacier centric models is that they are focussed on simulating glaciers that have been inventoried, i.e. they cannot retrieve past (or present) uncharted glaciers [43]. For these reasons, they are not well adapted for studying glacier evolution in climates when glaciers were widely different from today (e.g. the Last Glacial Maximum).

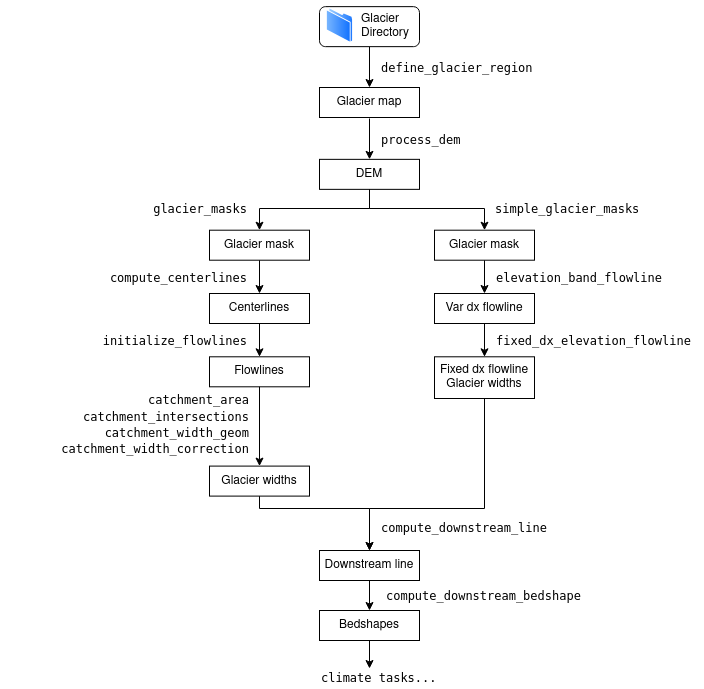

Standard modelling workflow¶

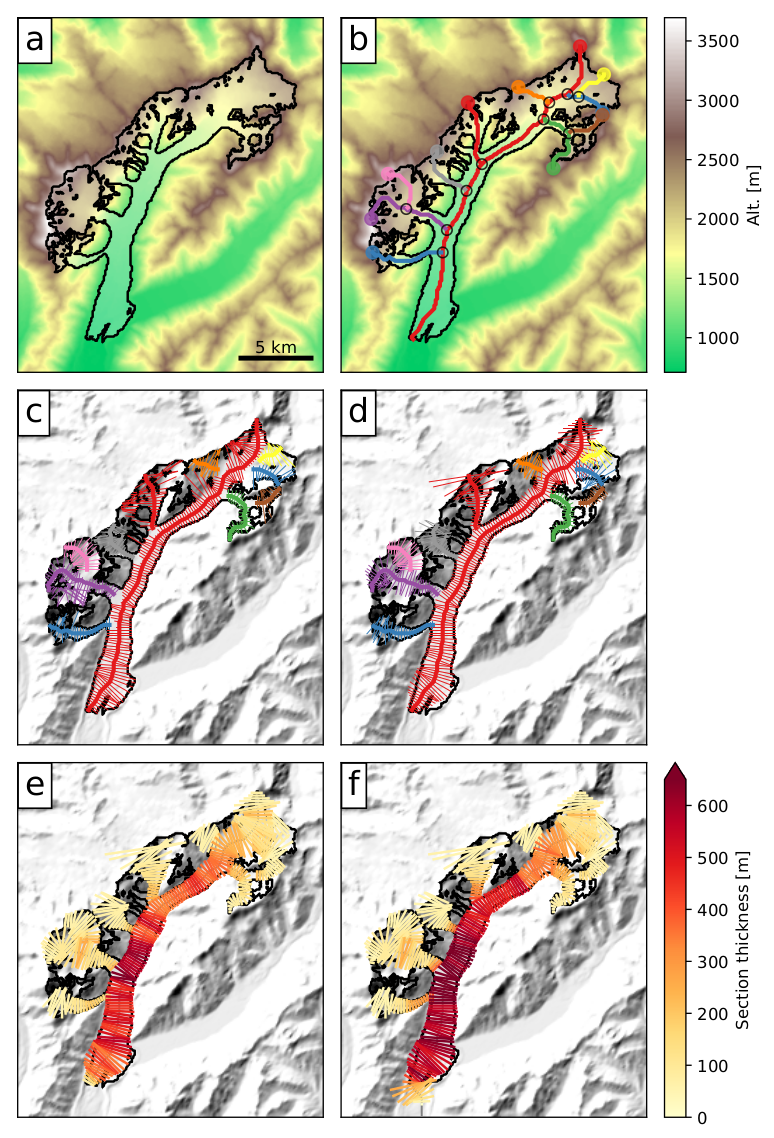

I briefly illustrate the OGGM workflow with an example application on the Tasman Glacier in New Zealand (see figure below). Refer to the model documentation for more information.

Preprocessing. The glacier outlines are extracted from a reference dataset (RGI) and projected onto a local gridded map of the glacier (Fig. a). Depending on the glacier location, a suitable source for the topographical data is downloaded automatically and interpolated to the local grid. The spatial resolution of the map depends on the size of the glacier.

Flowlines. The glacier centerlines are computed using a geometrical routing algorithm (Fig. b), then filtered and slightly modified to become glacier “flowlines” with a fixed grid spacing (Fig. c).

Catchment areas and widths. The geometrical widths along the flowlines are obtained by intersecting the normals at each grid point with the glacier outlines and the tributaries’ catchment areas. Each tributary and the main flowline has a catchment area, which is then used to correct the geometrical widths so that the flowline representation of the glacier is in close accordance with the actual altitude-area distribution of the glacier (Fig. d).

Climate data and mass balance. Gridded climate data (monthly temperature and precipitation) are interpolated to the glacier location and corrected for the altitude at each flowline’s grid point. A calibrated mass balance model is used to compute the mass balance for the past, and for projections based on GCM data.

Ice thickness inversion. Using the mass balance data computed above and relying on mass-conservation considerations, an estimate of the ice flux along each glacier grid point cross-section is computed by making assumptions about the shape of the cross-section. Using the physics of ice flow and the shallow ice approximation, the model then computes the thickness of the glacier along the flowlines and the total volume of the glacier (Fig. e).

Glacier evolution. A dynamical flowline model is used to simulate the advance and retreat of the glacier under preselected climate time series. Here (Fig. f), a 120-yrs long random climate sequence leads to a glacier advance.

Fig. 2 Illustration of the OGGM standard workflow applied to Tasman Glacier. Taken from Maussion et al., (2019).¶

OGGM data structures and glacier directories¶

The fundamental data structure used in OGGM is the so-called Glacier Directory. Glacier directories simply are folders on disk which store the input and output data for a single glacier during a run. OGGM offers an object interface to access and store these files programmatically.

This very simple idea is at the core of the OGGM workflow: actions to perform on glaciers (“tasks”, see below) are given access to the data files via the glacier directory interface, read data they need from disk, and write back to it.

This design matches perfectly the “glacier centric” modelling strategy, and has many advantages:

there is no practical difference between simulating one single, or many glaciers: all glacier directories are independent of another.

data is persistent on disk: workflows can be interrupted and restarted from disk at no cost overhead. Workflows can even be prepared on one computer and restarted from another computer (see example below).

“modularity” is achieved via data formats, not via programmatic interfaces: various ways to compute the flowlines (for example) can co-exist if they agree on how a flowline is stored on disk.

multiprocessing is trivial: the same task can be run on many glaciers at once without having to share data across processes, since everything is on disk and independant.

This persistence en disk has a few drawbacks as well:

for the glacier directories to be independent, several data sources are duplicated: topography for example (each glacier has its own subset of the original data, often overlapping with neighbors), or climate timeseries (the same data from the same grid point is stored in various directories). This can lead to rather large data storage requirements, but can be mitigated by deleting intermediate files.

since users can restart workflows from pre-processed states, the code that was used to produce them is often ignored or might be older, etc. This can lead to silent bugs (for example mismatching model parameters between the preprocessing and the simulations, leading to incorrect results). Because of this issue, we had to implement safeguards against such mistakes where possible.

users can be confused by glacier directories. Since an OGGM program does not always read like linear “A to Z” workflows (but for example “start from Q, then Q to Z”), mistakes like the ones described above can happen unnoticed.

it can make certain types of sensitivity experiments more difficult to implement, since users not only have to care about variable names, but also data file names.

Here is an example of how glacier directories work in practice. The user indicates a repository (base_url) from which

they want to fetch the data, and a list of glacier IDs they’d like to start from. The init_glacier_directories

performs the action of downloading and extracting these data locally.

from oggm import workflow, graphics

# Glaciers to simulate

rgi_ids = ['RGI60-11.01328', 'RGI60-11.00897']

# Where to fetch the pre-processed directories - this can be changed

server_url = 'https://cluster.klima.uni-bremen.de/~oggm/gdirs/'

experiment_url = 'oggm_v1.4/L3-L5_files/CRU/centerlines/qc3/pcp2.5/no_match'

base_url = server_url + experiment_url

# Fetch them

gdirs = workflow.init_glacier_directories(rgi_ids, from_prepro_level=3, prepro_base_url=base_url)

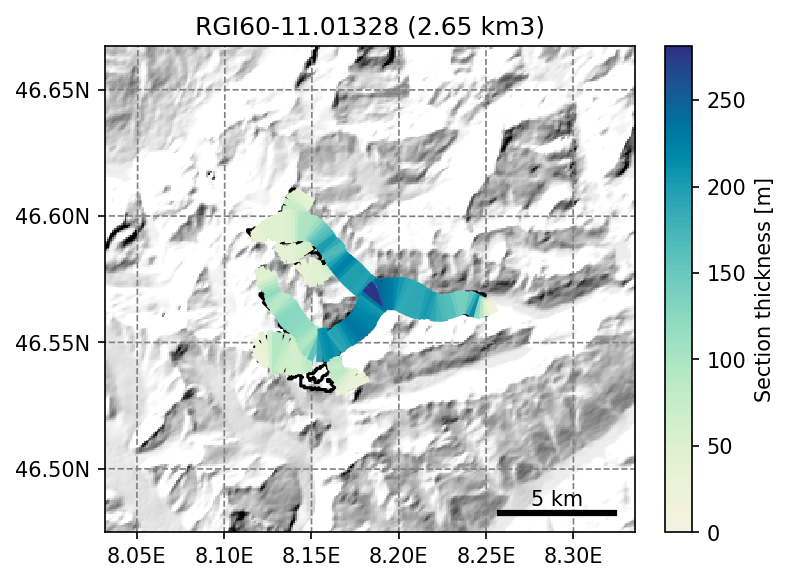

# Plot the ice thickness inversion results

graphics.plot_inversion(gdirs[0])

See also the documentation page for OGGM-Shop for more examples of the kind of data that can be added to glacier directories.

OGGM tasks¶

Tasks in OGGM are actions to perform on one single glacier (“entity tasks”) or several of them (“global tasks”). Tasks have a special meaning in the OGGM workflow and are applied as such:

# Initialize glacier dir

from oggm import workflow, tasks

ectories

gdirs = workflow.init_glacier_directories(rgi_ids)

# Define the list of tasks

task_list = [

tasks.define_glacier_region,

tasks.glacier_masks,

tasks.compute_centerlines,

tasks.catchment_area,

tasks.catchment_width_geom,

]

# Apply them sequentially

for task in task_list:

workflow.execute_entity_task(task, gdirs)

exectute_entity_task will apply the given task to a list of glaciers. If multiprocessing is switched on, all glaciers

will be processed in parallel, making full use of all available processors. Here we apply the default tasks with default

settings, but parameters can be changed via global settings or function arguments.

Depending on the desired set-up, tasks can be replaced by others (e.g. the centerlines tasks can be replaced by other algorithms) or omitted (for example, users can choose whether a quality check filter should be applied to the climate timeseries or not).

Take home messages¶

The purpose of this rather technical description was to convey the general design of the model around the concept of a list of tasks to be applied to glacier entities and that store their output in glacier directories on disk. Note that except for their names and the objects they are referring to (glaciers), these “building blocks” are largely agnostic to the kind of tasks that have to be applied, and I deliberately did not provide any modelling detail here.

This is important, because I believe that the OGGM project should not be considered by looking only at the physics choices we’ve made for each of these tasks or their default parameters. OGGM should also be evaluated for the new developments its structure can allow. OGGM does not enforce a particular modelling strategy beyond the constraints defined above: in summary, complying models do need to follow the glacier directory approach (otherwise OGGM will be of very little use for them). If new modelling groups develop ideas based on a glacier centric approach, they can make use of OGGM’s building blocks and add their own, provided that they comply with this “OGGM way of doing things”.

By doing so, external projects based on OGGM will then benefit from all future developments in OGGM, and the other way around: OGGM can then use and apply these external modules. If desired, external projects can also benefit from the suite of modern open development tools that OGGM provides. I describe them below.

Open development practices¶

OGGM development has been strongly inspired by practices which have become a standard in the software development community, but that are (unfortunately) not yet well known in the scientific community.

Like the vast majority of today’s software, OGGM’s development is done under a version control system called git. The OGGM repository is hosted on github, enabling many of the tools described below.

Code review¶

Very much like peer-review, open development practices based on git enable code review. Open code review has many advantages:

it gives model developers the opportunity to discuss changes alongside the code rather than per email

it improves code quality, since more than one person can look at the code

it gives an opportunity to model users to follow changes in the model even if they are not actively participating

code changes and associated comments over time are stored online for later reference

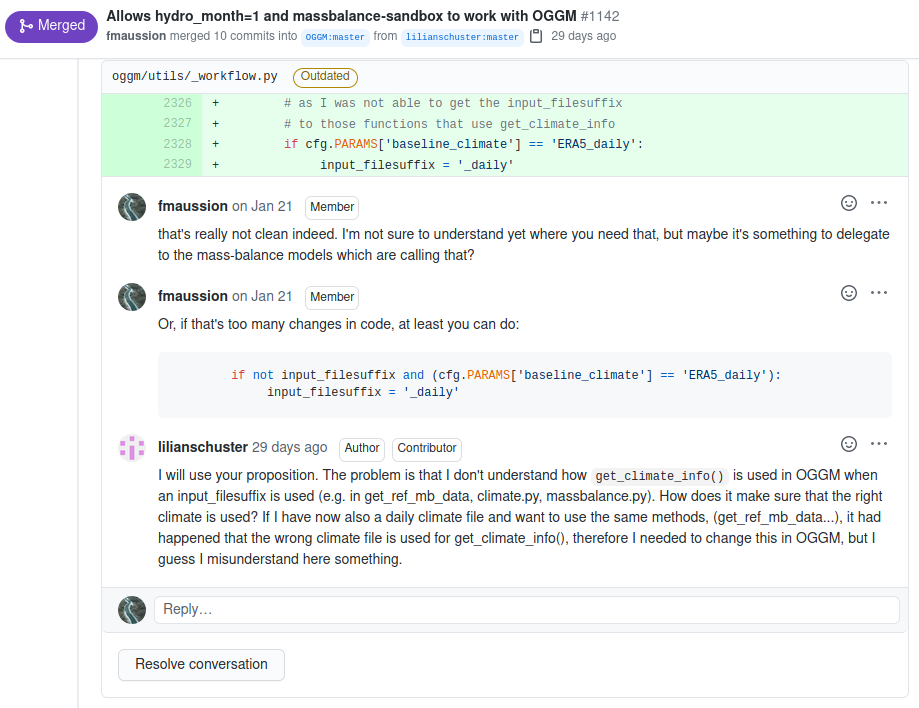

Fig. 4 Example of code review in a recent “pull-request”¶

Ideally, all code submissions to OGGM should be peer-reviewed. In practice, however, only the contributions from others than me are reviewed (by me). I’ll discuss this problem in more length below.

Testing strategy¶

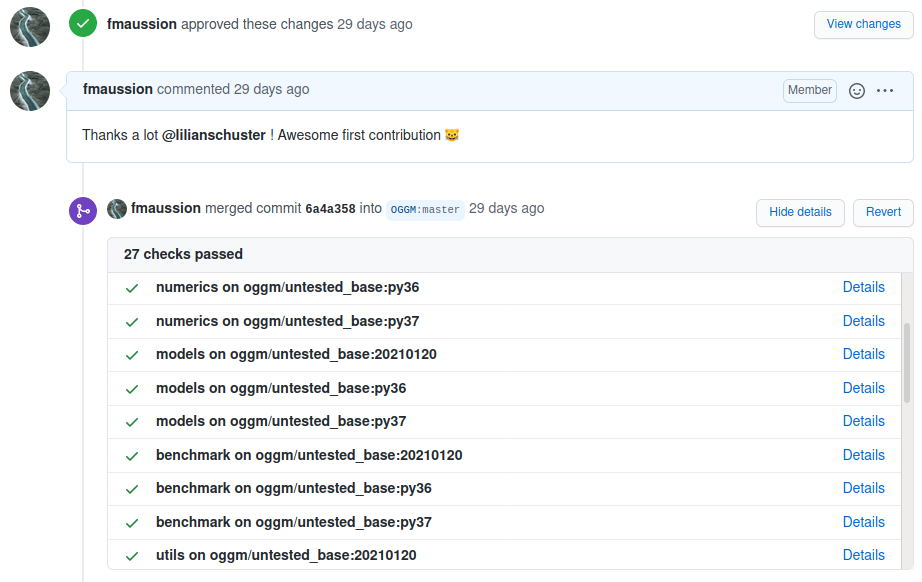

OGGM enforces a strict code testing strategy: all additions to the code must be supplemented by appropriate tests. The tests have the purpose to check that the code (i) can be executed without errors and (ii) works as expected. These tests are an integral part of the codebase, and all of them are run each time a new code addition is suggested (a process called continuous integration), hereby avoiding “regressions” as much as possible (when a change in one part of the code affects another in non-predictable ways).

Fig. 5 Example of automated testing in a recent “pull-request”¶

Online documentation and tutorials¶

Making code available is, by far, not enough to make code accessible. As of today, the OGGM codebase contains several thousands of lines of code, making it very difficult for anyone new to the project to understand the model’s structure just by reading the code.

Lack of code documentation (and the high cost of writing documentation) is probably one of the main obstacles towards more open code sharing practices, as many scientists do not feel comfortable to share undocumented code. OGGM is no exception (I always feel there could be better documentation for almost everything), but thanks to a suite of great open-source tools, writing documentation for OGGM can also be rewarding. Writing documentation is also a very good way to engage the community of users towards OGGM’s development, since contributing to the documentation can feel easier than contributing to the code.

OGGM’s documentation relies on three main elements:

The project website (https://oggm.org) for general, non code related project communication and blog posts.

The technical documentation (https://docs.oggm.org) to document model physics, model structure, and function calls definitions.

The tutorials (https://oggm.org/tutorials) with hands-on model applications in various use cases.

The project website is built using jekyll, a static site generator. It’s source code and content is also open and stored on github.

The technical documentation is built using sphinx and is hosted on readthedocs. Its content is stored alongside the code on the main repository.

The tutorials are written with Jupyter Notebooks and rendered online with Jupyter-Book. The notebook interface allows sharing text and formulas alongside the code, making them particularly adapted for tutorials. In addition, tutorials can be run and explored interactively thanks to MyBinder. This is a great tool to engage new users, since they can try the model online before going the struggle of installing it.

Fig. 6 Opening a tutorial in an interactive session in the browser¶

Reproducibility¶

OGGM attempts to make results obtained with the model reproducible as far as possible. To do so, the OGGM stable versions are stored with a DOI on Zenodo, and authors are encouraged to use and cite stable OGGM versions (we can also store older versions on demand if necessary).

Furthermore, a central tool that we offer to ensure that OGGM results are reproducible no matter the machine it is running on, or the version of software packages that are installed are docker containers. Containers are like a “software capsule”: they contain everything that OGGM needs to run and can be executed by any machine that has Docker installed.

Challenges¶

To my knowledge at the time of writing, OGGM has been used for at least 13 peer-reviewed publications (3 are in review) and has been an important part of 3 completed PhD theses. We expect these numbers to grow in the future, with new generations of students and new collaborations starting just now (see chapter 07). Several other indicators are suggesting that the OGGM project is being used by other research groups, such as the number of requests to join our discussion channels and to use OGGM-Hub.

The fact that the OGGM project is now expected to suit these various needs (new users with various expectations about OGGM capabilities, PhD students and PostDocs under time pressure, project deadlines, etc) comes with a number of challenges which I briefly describe here.

Technical debt¶

The OGGM code base has grown and continues to grow organically, at the pace at which new features are added to the model. Future innovation will be slowed down and maybe even impeded by the so-called “technical debt”: code that works but would need considerable refactoring to adapt to new ideas and to allow further development.

Accumulating technical debt also makes testing the software and ensuring the validity of its results more challenging. Certain functions might have been written in the past to take into account situations which are no longer an issue today, adding unnecessary complexity to the code.

This often needed refactoring (process of restructuring and modernizing existing computer code) is not without costs: it takes considerable time, is not rewarded by traditional academic measures such as publications, and needs to be carefully conducted in order not to introduce new bugs into the software. Perhaps even more problematically: existing users who wrote code based on OGGM are very unwilling to update it to the new OGGM versions (I know this from experience).

There is therefore a trade-off between breaking backwards compatibility (i.e. breaking existing code) and innovating. Other models with fewer users, or lower standards in terms of code reusability (this is not always a bad thing), may be more agile and quicker in innovating because no other people are relying on their code being stable.

Software maintenance and entry level for new contributors¶

A large part of routine software development maintenance currently relies on one or two main developers (myself, and an IT technician in Bremen who is in charge of the technical aspects of the deployment of OGGM). This work takes a lot of time (mainly because every new feature needs to be tested and documented), and my time is limited. Therefore, the development process is slower than I’d like it to be.

As the software grows and increases in complexity, it becomes more difficult for new users to understand the model’s structure and to apply it to their specific research problem. Furthermore, it makes it harder for new users to envision a potential contribution to the code base. The typical model contributors (PhD students and post docs) are employed on fixed-term contracts, causing a high turnover, making transmission of knowledge particularly difficult.

Finally, not all scientists are interested in writing reusable code, as is required when contributing to OGGM. Very few have the time, energy, or interest to invest in the rather demanding field of scientific programming, while staying on top of the other requirements of our job. I had the privilege to be given enough time to realize this project over the course of several years, thanks to my stable employment at the university of Innsbruck. No other traditional funding scheme in Austria would have allowed this kind of long haul development work.

The future of OGGM’s technical development and maintenance therefore strongly relies on funding agencies acknowledging that open-source development work is an integral part of the scientific process. Employers should reward open source work at the same level as scientific publications when considering applications.

Innovation with OGGM¶

I often ask myself the question of the role of OGGM in comparison to similar models in the geosciences. Let’s take the atmospheric model WRF as a prominent example. WRF is open-source, and its user base is obviously larger than OGGM by several orders of magnitude. The reason is not only that WRF is an atmospheric model, and a much more mature and feature complete model. I believe that a major reason is that users can take the model, learn how to use it (without knowing the internal details of its functioning), and apply it to their research question with very few modifications (change of domain, change of boundary conditions).

Attempting to make a parallel with OGGM will unravel some differences:

For one, OGGM already simulates all glaciers. I.e. “changing the domain” is not meaningful, unless the study attempts to simulate glaciers differently, or analyse the data from a new perspective.

Second, since OGGM is highly parameterized, applying it blindly, without a specific awareness of its simplifications and potential pitfalls, is not recommended. This point is also valid for WRF, but I would argue that it is less problematic: thanks to the large amount of available data for independent validation, users are able to check if their simulations are meaningful. With a model like OGGM, where the boundaries between calibration and validation data are fuzzier, it is difficult for users to assess whether they apply the model correctly or not.

Finally, application of OGGM to a new research question almost inevitably leads to the development of extensions to OGGM, or modifications of its internal code. This comes with the nature of the model: since the standard modelling of all glaciers is possible “out-of-the box”, innovation can only come with active participation in the model development, it’s capacity to deal with new boundary conditions, a new model parameterization, etc.

To summarize, and despite all our efforts to make OGGM user-friendly, I think that for the time being OGGM is still a model “for modellers”, not yet ready for blind application. Because of the nature of the problems that OGGM is trying to solve, it might never be “a model for users”, and remain “a model (or framework) for modellers”. I think that this is something I’d be happy with, but it has implications for the people willing to learn how to apply the model - in particular in terms of required programming and glacier modelling skills.