A very short introduction to Linux¶

This lecture is about programming, but it would be a big mistake to forget to talk about Linux here, at least a short introduction.

Every student in (geo-)sciences should know about the existence of Linux and know the basics of it. Atmospheric Sciences students in particular will have to use it sooner or later, since most of the tools and data they are using are running or have been created on Linux systems.

Table of Contents

- 1 A very short introduction to Linux

- 1.1 What is Linux?

- 1.2 Should I use it?

- 1.3 Testing Linux

- 1.4 The linux command line

- 1.4.1 Listing files and directories

- 1.4.2 The directory structure

- 1.4.3 Making Directories

- 1.4.4 Changing to a different directory

- 1.4.5 The directories . and ..

- 1.4.6 Copying files

- 1.4.7 Using [TAB]

- 1.4.8 Moving files

- 1.4.9 Removing files and directories

- 1.4.10 Displaying the contents of a file on the screen

- 1.4.11 Searching the contents of a file

- 1.4.12 Take home points

- 1.5 Executable scripts

- 1.6 The linux PATH

- 1.7 What's next?

What is Linux?¶

The web is going to give a better answer than me to this question.

Should I use it?¶

My very personal answer is a clear: yes! I can't force you to it though, and most of the exercises of this lecture can be done on a Windows computer too. If you are running Mac OS X then you have access to a linux terminal anyway and you can ignore my recommendation (even if I don't like Apple for several other reasons - totally subjective opinion again).

Linux has always been an environment for programmers and has the reputation of being "geeky" and "complicated". This is less true today, with many Linux distributions becoming mainstream and easy to use (my personal favorite is Linux Mint, but you probably mostly heard of Ubuntu which I also recommend).

I believe that Linux is much more user-friendly than Windows: once some of the particularities of Linux are understood (which can be frustrating in the beginning since it works quite differently than windows), it appears that there is much less "hidden" in Linux than in Windows (especially when it comes to installing/deinstalling software, using the command line, or protecting yourself from viruses and intruders).

As a scientist and programmer there are many reasons to prefer Linux (or Mac OS X) to Windows. Let me list some reasons here:

- Linux comes with many tools for scientists and programmers ("batteries included"). For historical reasons, Linux and its command line tools have been used by scientists and programmers since decades. It is not a surprise then that Linux comes with many (many) useful utilities to make programming and working with data easier.

- Linux is fast and reliable. Linux is extremely stable and more lightweight than Windows. I've never seen a Linux machine becoming slower with time, as I was used to see in my time using Windows (I have to admit: it was more than 10 years ago).

- Linux is the operating system of the huge majority of the super computers and web servers worldwide. Because of its efficiency, security, and multiple user management tools, Linux has taken over the web: 99.4% of the super computers and 67.5% of the web servers run Linux, while 79.3% of the mobile devices run Linux via Android.

- Linux is at the heart of the open-source philosophy. Linux is free and open-source, and it is not surprising that people who embraced the open-source philosophy also prefer Linux to Windows or Mac.

There are also some reasons not to use Linux of course. For one, Linux can be surprising at first and you'll need some time to get used to it. Also, it doesn't come pre-installed on most computers and you'll have to do it yourself (this is going to change: several retailers are already selling cheaper Ubuntu laptops to students). It is possible (but unlikely) that some of your hardware will not be compatible with Linux. Finally, some programs simply aren't available on Linux: Microsoft Office, the Adobe Suite, and games are the most prominent examples. The free and open-source alternatives (LibreOffice and GIMP) are good, but not as good as their commercial counterpart. I used Linux exclusively for more than 10 years now, and I never regretted it. Recently I had to install Windows in a virtual machine in order to use the MS Office software provided by the University, and it works perfectly. Another option is to use wine.

Testing Linux¶

Here are a few ways you can use Linux and make an idea by yourself:

- At the University of Innsbruck: In order to use Linux in the computer room you have to register for an account here. After an hour or so you will be able to connect to any computer using your username and password. The Linux distribution used at the university is CentOS (not my favorite I have to admit). If you are a student of another university, it is likely that you have access to Linux environments, too.

- On your laptop, with a live CD (or USB): this is the best way to try it at no risk and get a feeling for the general usage of a linux distribution. This is not permanent though.

- On your laptop, in a virtual machine: This is a relatively easy and non-destructive way to try Linux. There are tons of tutorials online, this one seems OK.

- On your laptop, alongside Windows (dual boot): this is a bit more engaged, but the best way if you want to use both operating systems at full capacity. See here for the official instructions. Be careful however: it is possible that things get a bit complicated going this way: secure your data first, and be prepared for some unexpected events.

- On your laptop, without Windows: Congratulations, this is the best solution! Please check that your hardware is compatible first, and follow the install instructions of your chosen OS. If you want to use Windows afterwards you can still re-install it or install it in a virtual machine.

The linux command line¶

Copyright notice: this section was largely inspired from the first parts of Michael Stonebank's UNIX tutorial

To open a terminal window, click on the "Terminal" icon from the Applications/System Tools menu. You can add an icon to your "quick launch" taskbar simply by dragging the icon to it.

A terminal window should appear with a $ prompt, waiting for you to start entering commands. The command line has a very important role in linux (as compared to windows where nobody uses it) since many tasks can be done much more efficiently with simple commands.

Listing files and directories¶

ls (list)

When you first login, your current working directory is your home directory. Your home directory has the same name as your username, for example, c7071047, and it is where your personal files and subdirectories are saved.

To find out what is in your home directory, type:

$ lsThe ls command lists the contents of your current working directory.

ls does not, in fact, cause all the files in your home directory to be listed, but only those ones whose name does not begin with a dot (.) Files beginning with a dot (.) are known as hidden files and usually contain important program configuration information. They are hidden because you should not change them unless you know what you do.

To list all files in your home directory including those whose names begin with a dot, type:

$ ls -aAs you can see, ls -a lists files that are normally hidden.

ls is an example of a command which can take options: -a is an example of an option. The options change the behaviour of the command. There are online manual pages that tell you which options a particular command can take, and how each option modifies the behaviour of the command. ls -lh is an other way to call ls with two options, l for "listing format" and h for "human readable".

Note: linux file names and commands are case sensitive, i.e. Test.txt is different from test.txt, and both names could coexist in the same directory.

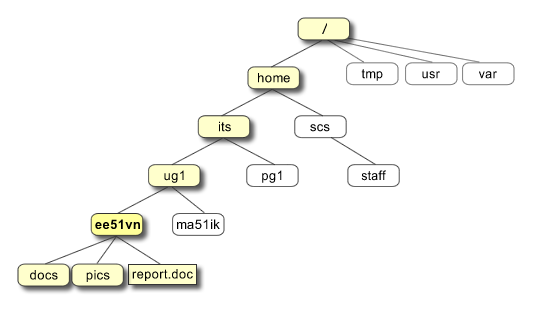

The directory structure¶

All the files are grouped together in the directory structure. The file-system is arranged in a hierarchical structure, like an inverted tree. The top of the hierarchy is traditionally called root (written as a slash / )

When loging in we are automatically located in our personal home directory, which is aptly named because:

- we won't need to leave

homeduring our exercises - we are allowed to do whatever we want in our

home, while we are not allowed to write, delete or change things in the other directories.

To know where we are in the directory structure, there is a useful command:

$ pwdwhich prints the path of the current working directory.

Making Directories¶

mkdir (make directory)

We will now make a subdirectory in your home directory to hold the files you will be creating and using in the course of this tutorial. To make a subdirectory called unixstuff in your current working directory type:

$ mkdir unixstuffTo see the directory you have just created, type:

$ lsChanging to a different directory¶

cd (change directory)

The command cd directory means change the current working directory to "directory". The current working directory may be thought of as the directory you are in, i.e. your current position in the file-system tree.

To change to the directory you have just made, type:

$ cd unixstuffType ls to see the contents (which should be empty)

Exercise: make a directory called

Exercise: make a directory called backup in the unixstuff directory

The directories . and ..¶

Still in the unixstuff directory, type:

$ ls -aAs you can see, in the unixstuff directory (and in all other directories), there are two special directories called (.) and (..)

The current directory (.)

In linux, (.) means the current directory, so typing:

$ cd .means "stay where you are" (the unixstuff directory).

This may not seem very useful at first, but using (.) as the name of the current directory will save a lot of typing, as we shall see.

The parent directory (..)

(..) means the parent of the current directory, so typing:

$ cd ..will take you one directory up the hierarchy (back to your home directory). Try it now.

Note: typing cd with no argument always returns you to your home directory. This is very useful if you are lost in the file system.

~ (your home directory)

Home directories can also be referred to by the tilde ~ character. It can be used to specify paths starting at your home directory. So typing:

$ ls ~/unixstuffwill list the contents of your unixstuff directory, no matter where you currently are in the file system.

Copying files¶

cp (copy)

cp file1 file2 is the command which makes a copy of file1 in the current working directory and calls it file2

What we are going to do now, is to take a file stored in an open access area of the file system, and use the cp command to copy it to your unixstuff directory.

First, cd to your unixstuff directory:

$ cd ~/unixstuffThen type:

$ cp /scratch/c707/c7071047/tuto/science.txt .Note: Don't forget the dot . at the end. Remember, in linux, the dot means the current directory.

The above command means "copy the file science.txt to the current directory, keeping the name the same".

Note: The directory /scratch/c707/c7071047/tuto is an area to which everyone in the University has read and copy access. If you are from outside the University, you can grab a copy of the file from the internet. For this, you can use another very useful command, wget:

$ wget http://www.ee.surrey.ac.uk/Teaching/Unix/science.txtThis will download the file science.txt to your current directory

Exercise: Create a backup of your

Exercise: Create a backup of your science.txt file by copying it to a file called science.bak

Note: directories can also be copied with the -r option added to cp.

Using [TAB]¶

[TAB] is very useful in the Linux (and other) command line: it use an automated completion algorithm to complete the commands you are typing. For example, try to type $ cd ~/uni and then TAB. This is also going to make suggestions in case of multiple choices, or for commands.

Moving files¶

mv (move)

mv file1 file2 moves (or renames) file1 to file2

To move a file from one place to another, use the mv command. This has the effect of moving rather than copying the file, so you end up with only one file rather than two.

It can also be used to rename a file, by moving the file to the same directory, but giving it a different name.

We are now going to move the file science.bak to your backup directory.

First, change directories to your unixstuff directory. Then type:

$ mv science.bak backup/Type ls and ls backup to see if it has worked.

Removing files and directories¶

rm (remove), rmdir (remove directory)

To delete (remove) a file, use the rm command. As an example, we are going to create a copy of the science.txt file and then delete it.

Inside your unixstuff directory, type:

$ cp science.txt tempfile.txt

$ ls

$ rm tempfile.txt

$ lsYou can use the rmdir command to remove a directory (make sure it is empty first). Try to remove the backup directory. You will not be able to since linux will not let you remove a non-empty directory. To delete a non-empty directory with all its subdirectories you can use the option -r (r for recursive):

$ rm -r /path/to/some/directoryThis command will then ask you confirmation for certain files judged important. If you are very sure of what you do, you can add a -f to the command (f for force):

$ rm -rf /path/to/some/directory/that/i/am/very/sure/to/deleteNote: directories deleted with rm are lost forever. They don't go to the trash, they are just deleted.

Displaying the contents of a file on the screen¶

clear (clear screen)

Before you start the next section, you may like to clear the terminal window of the previous commands so the output of the following commands can be clearly understood.

At the prompt, type:

$ clearThis will clear all text and leave you with the $ prompt at the top of the window.

cat (concatenate)

The command cat can be used to display the contents of a file on the screen. Type:

$ cat science.txtAs you can see, the file is longer than than the size of the window. You can scroll back but this is not very useful.

less

The command less writes the contents of a file onto the screen a page at a time. Type:

$ less science.txtPress the [space-bar] if you want to see another page, and type [q] if you want to quit reading. As you can see, less is used in preference to cat for long files.

head

The head command writes the first ten lines of a file to the screen.

First clear the screen then type:

$ head science.txtThen type:

$ head -5 science.txtWhat difference did the -5 do to the head command?

tail

The tail command writes the last ten lines of a file to the screen.

Clear the screen and type:

$ tail science.txt Exercise: How can you view the last 15 lines of the file?

Exercise: How can you view the last 15 lines of the file?

Searching the contents of a file¶

Simple searching using less

Using less, you can search though a text file for a keyword (pattern). For example, to search through science.txt for the word "science", type:

$ less science.txtthen, still in less, type a forward slash [/] followed by the word to search:

/scienceAnd tape [enter]. Type [n] to search for the next occurrence of the word.

grep

grep is one of many standard linux utilities. It searches files for specified words or patterns. First clear the screen, then type:

$ grep science science.txtAs you can see, grep has printed out each line containg the word science.

Or has it ????

Try typing:

$ grep Science science.txtThe grep command is case sensitive; it distinguishes between Science and science.

To ignore upper/lower case distinctions, use the -i option, i.e. type:

$ grep -i science science.txtTo search for a phrase or pattern, you must enclose it in single quotes (the apostrophe symbol). For example to search for spinning top, type:

$ grep -i 'spinning top' science.txtSome of the other options of grep are:

-vdisplay those lines that do NOT match-nprecede each matching line with the line number-cprint only the total count of matched lines

Try some of them and see the different results. Don't forget, you can use more than one option at a time. For example, the number of lines without the words science or Science is:

$ grep -ivc science science.txtTake home points¶

We have only shown some examples of how to navigate in the linux directory structure and use some simple commands. This is by far not sufficient to demonstrate its usefulness: the grep command for example is extremely powerful to help you find files that you thought you had lost, and wget a file to a current directory is often much faster than downloading it in firefox and copy it afterwards. For the time being, this short tutorial should help get you started.

To go further, I recommend to follow Ryan's linux tutorials, they are excellent!

Executable scripts¶

Now that you are familiar with the command line, you must have noticed that linux commands have some similarities with the statements you used in your bachelor programming course: by typing them in, the computer does things for you and gives you information back (often printed on screen, but not always). When you want to automate a series of commands you just typed in (for example renaming and moving files), a natural thing would be to write a script to do so.

Scripts are the simplest type of program one can write, and this can be seen as your first programming experience in this course. We are going to write a bash script and execute it: why we want to do this in a python scientific programming course may be not clear right now, but it will make more sense later I promise.

A simple script¶

In your unixstuff directory, create a new file name myscript.sh. You can do this using the default (graphical) text editor in linux, gedit. At the command line:

`

$ gedit myscript.shJust type one simple line in the file:

echo Hello World!Quit your editor and go back to the command line again. You can execute your script with the following command:

$ bash myscript.shBash is a so-called "interpreter". It reads your file and understands how to execute the commands in it.

Make a file executable¶

List the files in your directory, but whith the option -l for more information. Here is how it looks like on my computer:

mowglie@flappi-top ~/Documents/unixstuff $ ls -l

total 28

drwxrwxr-x 2 mowglie mowglie 4096 Feb 22 18:05 backup

-rw-rw-r-- 1 mowglie mowglie 19 Feb 22 18:44 myscipt.sh

-rw-rw-r-- 1 mowglie mowglie 7767 Sep 1 2000 science.txtThe first list of characters indicate the file's permissions. Now read the first section of Ryan's tutorial about permissions. So what do we learn from the above? That the file's owner (myself) is allowed to read and write the myscript.sh file, but not to execute it. Let's change this:

$ chmod a+x myscipt.shNow everybody (including me) is allowed to execute this file. It is a quite harmless script, so I'm not too worried. Now we can execute it:

$ ./myscript.shNice! We could add much more commands to our script (possibly making it more useful), but this was enough to illustrate the point I wanted to make: files can be executable in Linux, and a whole new world opens to us.

Note: Most often, it is recommended to add a specific first line to your script, called a shebang. This line tells the computer which interpreter should be used to run the file. In our case it is the default interpreter (bash), but this may not always be the case. To be entirely explicit, we recommend to always add a shebang to your script. In this case, we should add #!/bin/bash to our script:

#!/bin/bash

# Maybe some comment line about the purpose of this script

echo Hello World!Take home points¶

It is possible to write simple programs in linux called "scripts". These scripts can be executed by the default interpreter, and be made "executable" very easily. If you want to know more about bash scripts, read Ryan's tutorial about the subject!

The linux PATH¶

Locate linux programs¶

You may have asked yourself: how does the linux command line know about the commands we are using? Where do I find them? A nice program helping us to find out is which. Let's use it:

$ which less

/usr/bin/lessNow we can use another command, whatis, to tell us what we just did:

$ whatis whichThe which command tells us that the less program is located in /usr/bin. We can also ask which where to find which:

$ which which

/usr/bin/which

$ ls -l /usr/bin/which

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 10 Nov 19 14:42 /usr/bin/which -> /bin/whichAs expected, which is an executable file. Some executables are binary files (i.e. not human readable), but in this case which is actually a script:

$ less which Exercise: scroll through the script. Can you locate the shebang line? How does the code look like to you: easily understandable, or rather cryptic?

Exercise: scroll through the script. Can you locate the shebang line? How does the code look like to you: easily understandable, or rather cryptic?

The PATH variable¶

The linux command line knows so-called environmental variables. The echo command can display their value:

$ echo $PATH(the $ tells echo to display the value of the variable PATH rather than its name). The PATH variable contains a list of paths, separated by semicolons. It is an extremely important variable: it tells linux where to look for executables and programs. Each time you type a command, linux will look in the PATH and see if it finds it. This is an extremely flexible and powerful system, as we are going to see in the next chapter (Installing Python).

The PATH can be extended to contain any other directory you find useful to add. Let's do it:

$ mkdir ~/myprograms

$ export PATH=$PATH:~/myprogramsexport creates a new variable called PATH (in this case, it overwrites the existing PATH).

Exercise: now move your executable script

Exercise: now move your executable script myscript.sh in the myprograms directory. Verify that you can now execute the myscript.sh program from any directory.

Note: we have extended the PATH variable in this session only. If you close and reopen the terminal the changes will be lost. There are ways to make these changes permanent, we will learn them in the next chapter.

Note: if a program is listed in several path directories, linux takes the first instance. Directories can be prepended and appended, as we will see in the next chapter.

Take home points¶

The PATH variable tells linux where to look for programs and scripts. This is a very simple and powerful way to customize linux with your own scripts and programs. We are going to use this feature to install Python in the next chapter.

What's next?¶

Back to the table of contents, or jump to the next chapter.