Scientific Programming - old lecture!¶

Fabien Maussion, July 2018

Lecture notes of the master lecture 707716 - Scientific Programming, given in the summer term 2018.

These lecture notes are kept for documentation and historical purposes only! For the latest version visit:

https://fabienmaussion.info/scientific_programming

If you're not here for the first time, jump to:

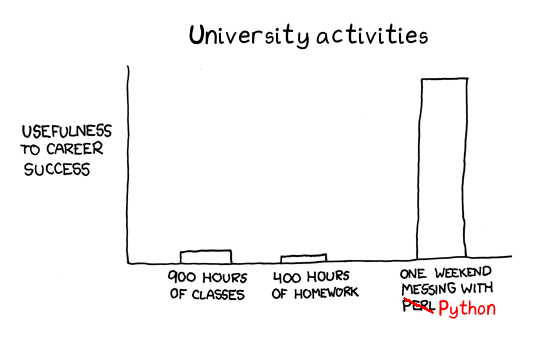

Adapted from xkcd. The xkcd author Randall Munroe would probably agree with my changes.

Preface¶

There are plenty of excellent resources to learn python available (see references below). So why writing this "book"? Well, for one, because none of them is organized to fit exactly the 15 week semester of Austrian universities. Therefore I had to make some choices regarding (i) what to teach and (ii) how to teach it. However, there is no need in reinventing the wheel and rewriting what much better teachers wrote before me: as you will see, I will rely heavily on external resources, all openly available. Following the open source philosophy, these lecture notes are also freely available.

These notes are written on the go, as this course advances. I am trying to write them in such a way that they are understandable without actually attending the course, but this takes time and if I'm getting late on schedule I might revisit this goal. In that case I'll have to come back to them later ;-).

Learning outcomes of this course¶

This class aims at learning modern programming techniques for (geo-)scientists. After finishing the class, attendees should understand how numbers are handled by computers and be aware of numerical accuracy errors. They should be able to program in a structured, extendable and reproducible manner. In the process of this class students will get acquainted with various programming tools (IDEs, debugger, unit testing, object oriented programming, version control, open development practices).

The targeted audience for this lecture are (geo-)sience students at the master level with previous experience in programming. No prior knowledge of python is required, but I'll assume that you are familiar with a similar language (Matlab, IDL, R...). This is not an introductory course, although we will shortly revisit the basics in order to learn the python syntax.

The course encompasses the following topics, which are developed by means of concrete examples in the Python programming language:

- Introduction to Linux

- Semantics: revisiting and formalizing the basic programming structures (loops, functions, conditional blocks...)

- General programming concepts, differences between compiled and interpreted languages

- Numerics: floating point numbers, N-dimensional arrays

- Software structure: packages, modules, functions, scripts

- Object oriented programming: fundamentals, usage, and basic design patterns

- Code testing and version control

- Real world applications!

Frequently Asked Questions¶

What is "Scientific Programming"?¶

Scientific programming targets to solve scientific problems with the help of computers. It is sometimes used as synonym for computational science, but in my opinion these are not entirely the same. "Scientific programming" is not really a discipline, and therefore cannot be taught.

What are we doing here then? Well, we are going to learn programming first, and then programming as a tool to do science. We are going to apply our new skills to scientific problems, but not only. Within the time given to us (14 units) we won't be able to learn everything about programming of course. My hope is that at the end of the lecture you'll have sufficient background and tools at your disposition to solve your own problems, and (this is the most important bit) that you'll know where to find solutions to the problems you encounter.

Why should I learn programming?¶

As a scientist you are going to either produce or analyze data, most of the time you'll do both. For a long time, scientists have seen programming as a "tool", a menial task to accomplish in order to answer the questions they were asking. Nowadays programming has taken a prominent place in a scientist's work, for several reasons:

- the amount of data we have to handle increases together with computational power and our capacity to store it. I would even argue that the bottleneck in model based scientific discovery isn't the computational effort anymore, but our capacity to comprehend and analyze these huge amounts of data.

- the questions we are asking are getting more complex, and so are the tools we are using to answer them. The times when scientists could make discoveries with the help of a piece of paper and a pen are long gone, at least for most of us in the geosciences. We rely heavily on computer models, and these models are developed by us scientists, not only by programmers.

- science faces a credibility crisis, and part of the mistrust towards scientists comes from the fact that their research happens behind closed doors, using closed source tools and based on protected data. Opening our computers and demonstrating that our code can be trusted is necessary to re-engage confidence in our results.

- on a more general note: a better understanding of the tools that govern our digital world is a strong asset for many aspects of our everyday life and citizenship.

In simple words, we have to become better programmers to be faster and better at what we do: science.

Why Python?¶

We will use the Python programming language in this course. In case you are wondering why this language and not any other like <name your favorite language here>, let me stop you right away: this course is not about "learning Python", it is about learning the general concepts of programming: algorithmic, numerics, program structure, object oriented programming, testing, etc. Python is just the tool I chose to use for this purpose.

We could indeed have taken any other language, but there are several advantages in using Python. A quick web search will give you millions of reasons, but let me pick some of my favorites here:

- Python is a general purpose programming language and, as such, well suited to learn general programming concepts. It is therefore better suited than, for example, R which was developed for statistics and has certain particularities regarding object oriented programming in particular.

- Python can be used for many purposes, from data preprocessing to numerical modeling and plotting. Unless you have a very compelling reason to change, you are likely to be able to use Python for all programming tasks you'll have in the near future.

- Python is one of the fastest growing languages for data science. There is a very active community developing new and exiting packages every day, and joining this community is surely a good bet on the future.

- Python is free and open-source. No license fee, the code is available for everyone to see.

There are many other reasons to use Python (and some arguments against Python as well of course), but I don't think it's relevant to list them here. My argument is following: for a good programmer, switching language is not a very big deal. It's not easy of course, but it's possible - becoming a good programmer is the hard bit, and is a never ending process.

Course contents¶

- Week 01: Introduction, Install Python, Getting Started

- Week 02: The Python language and the standard library

- Week 03: Good practices in programming, exceptions and testing

- Week 04: Floating point arithmetics

- Week 05: Numpy

- Week 06: Scientific Python

- Week 07: Python packages

- Week 08: Object Oriented Programming (Part I)

- Week 09: Object Oriented Programming (Part II)

- Week 10: Code documentation, open source

How to use these notes¶

These notes are written as a companion to the lectures. During the lectures I will go through the major concepts (using slides, the good old way), and the notes are here to help you learn at home. In an ideal world the notes should be usable without me paraphrasing them out loud, but this will depend on the time I have to write them along the way.

The notes are a mix of examples and small exercises. The exercises can happen in between the examples and are marked with a question mark logo. If you want to download the notebooks I used to write the notes, you will find them on the course's repository.

At the end of each unit there will be an assignment. These can be worked through alone or in groups. Each week, I will ask one group to present their results to the rest of the class.

The class grants you 4 ECTS if successfully passed: in theory, this represents about 6 hours work per week (not including holidays). For this course it is expected that you spend at least as much time doing homework than sitting in class.

When you will be going through the examples of these notes, some sentences are marked in bold: this underlines their importance for the course. When single words are bold this symbolizes new concepts or new definitions: they need to be understood (and googled if needed).

External resources¶

Resources used (and linked) in these lecture notes:

Linux and bash scripting:

- Ryan's Tutorials for the linux command line and bash scripting are entertaining and well designed.

Python tutorials:

- the official tutorial, always a good place to start.

- the scipy lecture notes, a good overview of the scientific python stack for scientists with previous programming experience.

Python reference:

- the python documentation is your best reference for any question related to the language and the standard library.

Testing

- Katy Huff's scientific python testing tutorial: a one and a half hour introduction to testing practices, from the basics to continuous integration

Floating point precision errors

- Python's Floating Point Arithmetic article is a good read but a bit tough for beginners

- What Every Programmer Should Know About Floating-Point Arithmetic is a more gentle introduction, but you still might want to use a search engine for more information.

Numpy

- Why python is slow by Jake Vanderplas

- From Python to Numpy by Nicolas P. Rougier: an open-access book on numpy vectorization techniques (rather advanced).

- The numpy reference: the official documentation is always the best place to obtain first hand information.

Scientific Python

- Python Data Science Handbook by Jake Vanderplas: an open-access textbook on using Python for Scientists

Python namespaces and scopes

- blog post by Sebastian Raschka: A Beginner's Guide to Python's Namespaces, Scope Resolution, and the LEGB Rule

Object Oriented Programming The web is full of blog posts and basic tutorials about OOP in python. Unfortunately, most of them make a poor job at explaining why OOP can be useful and when not. I will try to find better resources, but for now I recommend:

Documentation

(this list will be updated when the notes get written further)

Getting help¶

Seeking for information online is necessary and helpful at any level of programming skills. I would even argue that good programmers are the ones who know how to efficiently find information online.

When encountering an issue, the first question you should ask yourself is: "am I the only one to be affected by this problem/obstacle?". The answer will be no in 99% of the cases. For these cases, here is a list of recommendations:

- Stack Overflow is THE place for programming questions. Thanks to community based moderation rules, the good questions are more visible than bad ones, and good answers are rewarded. Take a tour of the site's principles now, and look for similar questions there before asking your own question.

- Learn to ask the right question to your search engine. Naming this the correct way (semantics) is one of of the objectives of this lecture, and I hope that in the end you will not only write better code, you will also speak the programming language a little better.

If every other thing fails (i.e the remaining 1%), than:

- Ask a question on Stack Overflow. Before doing so, read what a Minimal, Complete, and Verifiable Example is and try to stick to these recommendations.

- If you think you discovered a bug, than report it to the library directly. Almost all the scientific python packages are hosted on GitHub: the "issues" tab is where to report bugs. Read the excellent Craft Minimal Bug Reports article from Matt Rocklin before doing so.

Authors¶

- Fabien Maussion wrote these notes (unless specified otherwise, e.g. for some tutorials)

- Matthias Göbel (student assistant at the time of writing) reviewed and proof read them

License¶

These lecture notes and exercises are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Feel free to use / adapt them, but don't sell them, and share them under the same licence.