The scientific python stack¶

Unlike Matlab, the set of Python tools used by scientists does not come from one single source. It is the result of a non-coordinated, chaotic and creative development process originating from a community of volunteers and professionals.

In this chapter I will shortly describe some of the essential tools that every scientific python programmer should know about. It is not representative or complete: it's just a list of packages I happen to know about, and I surely missed many of them.

Python's scientific ecosystem¶

The set of python scientific packages is sometimes referred to as the "scientific python ecosystem". I didn't find an official explanation for this name, but I guess that it has something to do with the fact that many packages rely on the others to build new features on top of them, like a natural ecosystem.

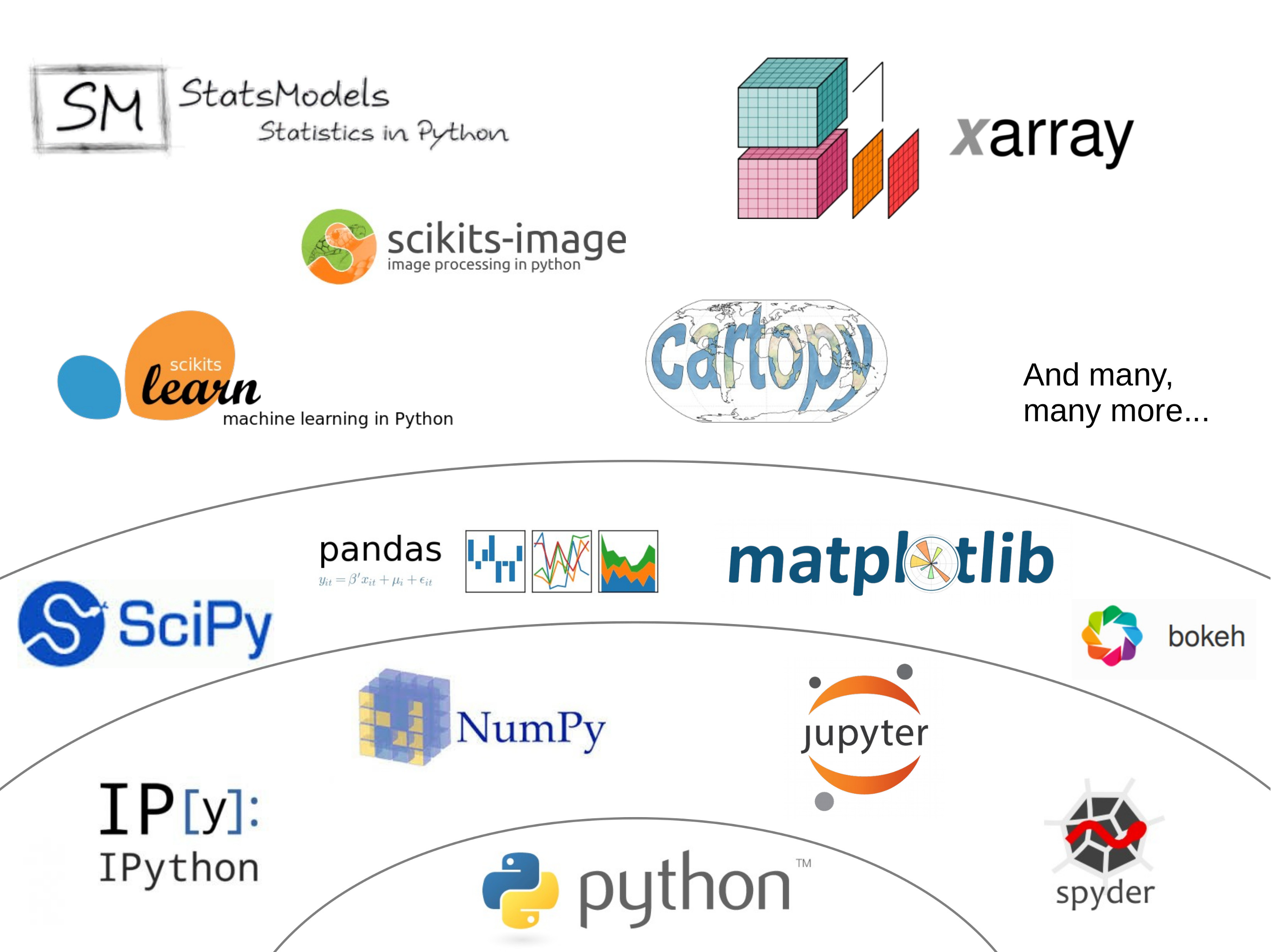

Jake Vanderplas made a great graphic in a 2015 presentation (the video of the presentation is also available here if you are interested), and I took the liberty to adapt it a little bit:

The core packages¶

The entire scientific python stack relies on two core packages:

- numpy: documentation, code repository

- scipy: documentation, code repository

- matplotlib (documentation, code repository

Numpy provides the N-dimensional arrays necessary to do fast computations, and SciPy adds the fundamental scientific tools to it. SciPy is a very large package and covers many aspects of the scientific workflow. It is organized in submodules, all dedicated to a specific aspect of data processing. For example: scipy.integrate, scipy.optimize, or scipy.linalg. Matplotlib is the traditional package to make graphics in python.

Development environments¶

Development environments are not "python packages" per se, but they are helping you to write better code faster. Here are some of them:

- ipython: an extended python command line, but much nicer to use (documentation, code repository). Originally developed by the scientific python community, it it now used by many developers as well.

- jupyter notebook: built on top of ipython, the jupyter notebook gives you access to an ipython interpreter in your browser (documentation, code repository). It allows you to write code and display its output in the same page, which is very useful for communicating your results or documenting code. As a development environment, however, the notebook quickly reaches its limits.

- spyder: designed to look like the Matlab IDE, spyder is mostly used by scientists (documentation, code repository). Because it is a non-funded community project it has some rough edges, but altogether it works great!

- atom is a general purpose text editor (documentation, code repository). It is very fancy and lightweight, and has a lot of plugins for whatever you are using the editor for.

- pycharm is a closed-source, professional IDE with a community version available for free. It has more features than spyder but is is also much more resource hungry. I use pycharm community edition in my work.

Essentials¶

There are two packages which I consider essential when it comes to data I/O (input/output) and data analysis:

- pandas provides data structures designed to make working with labeled data both easy and intuitive (documentation, code repository).

- xarray extends pandas to N-dimensional arrays (documentation, code repository).

They both add a layer of abstraction to numpy arrays, giving "names" and "labels" to their dimensions and the data they contain.

Domain specific¶

# TODO

What's next?¶

Back to the table of contents, or jump to this week's assignment.