From Skaftafell to Hverfisfljót, Day Two

Blátindur – Skeiðarárjökull

We wake up to two small holes in the part of our tent where we had pressed our feet against stones during the night in order not to slide down. We had piled up those stones for slightly more wind protection but had forgotten to look for sharp edges pointing in the wrong direction. Oh well, nothing else to do than to close the wounds of our new tent (light but sensitive) with some duct tape. Good start!

Other than that, we feel recovered and a grey-blueish weather promises good conditions for the glacier traverse. By day we can now clearly see the ridge that will lead us all the way to the edge of Skeiðarárjökull – not a short walk and somewhat exposed but compared to the day before a rather nice scramble with insane views over the glacier.

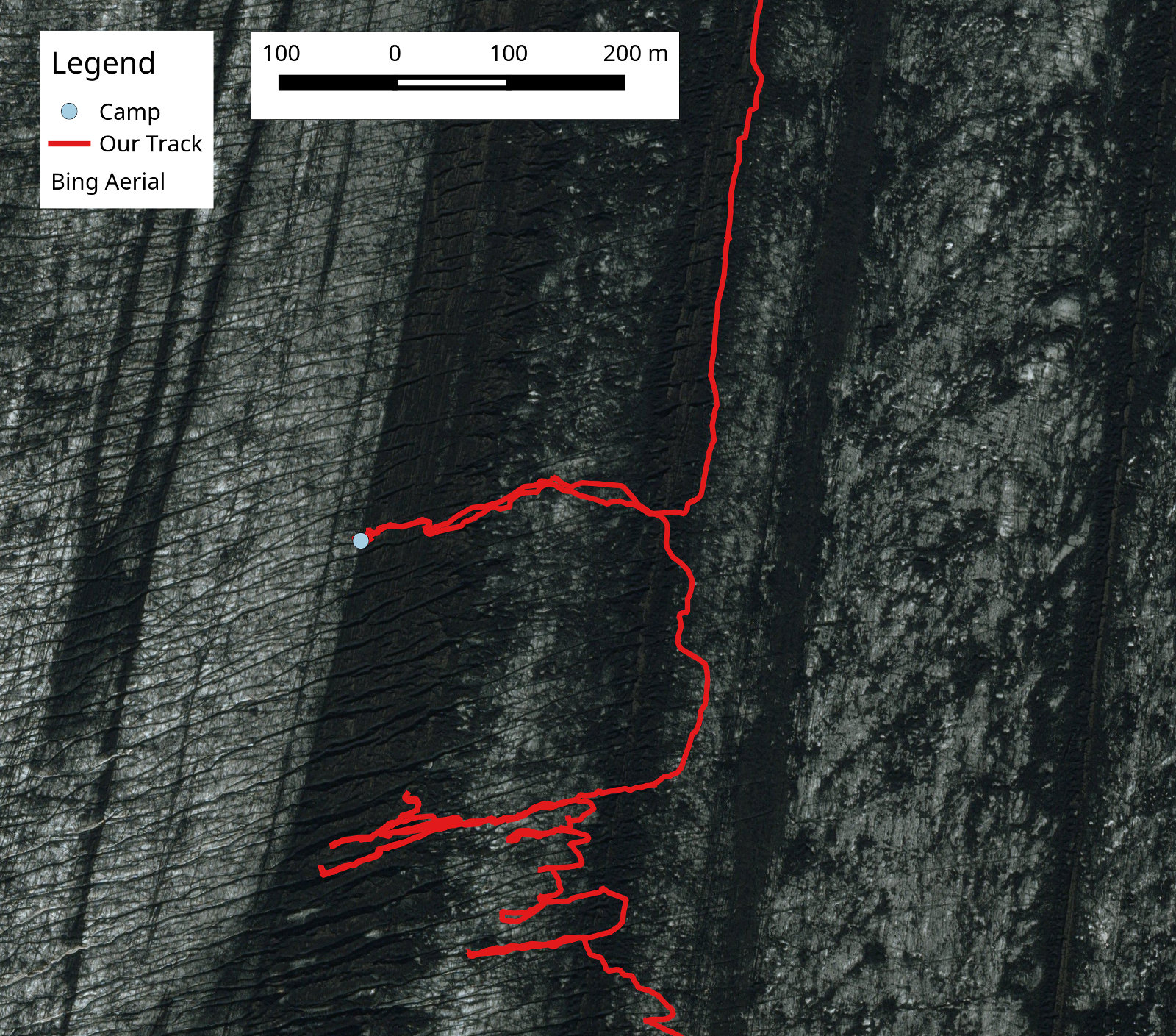

Two snow fields and one steep moraine later we finally reach a point that allows easy passage onto Skeiðarárjökull, avoiding large meltwater lakes at the glacier edge reaching further eastwards. We put on our crampons – in view of the rugged glacier surface we’re glad that we’ve taken them: carrying this extra weight won’t have been for nothing! In addition to our GPS tracks and the hiking map, we had printed out two crevasse maps indicating “danger zones” for both glaciers on our way. Therefore, we already knew we could expect a rather friendly glacier to start with, gradually developing into a very hostile environment. But we hadn’t expected such a clever, subtle monster with an unbelievable determination to keep us away, to slowly crush our spirit rather than our bodies.

However, unknowing what exactly is lying ahead, we start our traverse in full sunshine and in a very good mood. The glacier surface is becoming rougher and rougher, forcing us to bounce up and down over ever growing ice bumps. Fabien rushes over the ice in impressive speed, taking bumps in long strides without having to climb up or down. Conni on the other hand, given her considerably shorter legs, has to jump around between these bumps slowing her down and wearing her out. The bumps keep growing, just like the crevasses do. More and more of them, springing open to the left and the right, making us feel like in a labyrinth for the first time, making Fabien nervous.

At this point it’s worth to point out that Conni had secretly expected to spend a night on this glacier right from the start. We had reached Skeiðarárjökull at around 1pm and although there was no way of knowing exactly how challenging this traverse would be, the glacier has the atmosphere of someone who won’t let go of you quite so easily. Fabien on the other hand, being the glaciologist he is, felt more optimistic and was therefore prone to a deeper fall in terms of morale. Struggling with finding a way through the first heavily crevassed section (orange on the glacier map) he exclaimed his first “Oh Conni, this doesn’t look good” (it wouldn’t be the last one). This in itself is quite funny in hindsight since that section was absolutely nothing compared to the true grim face that was waiting for us.

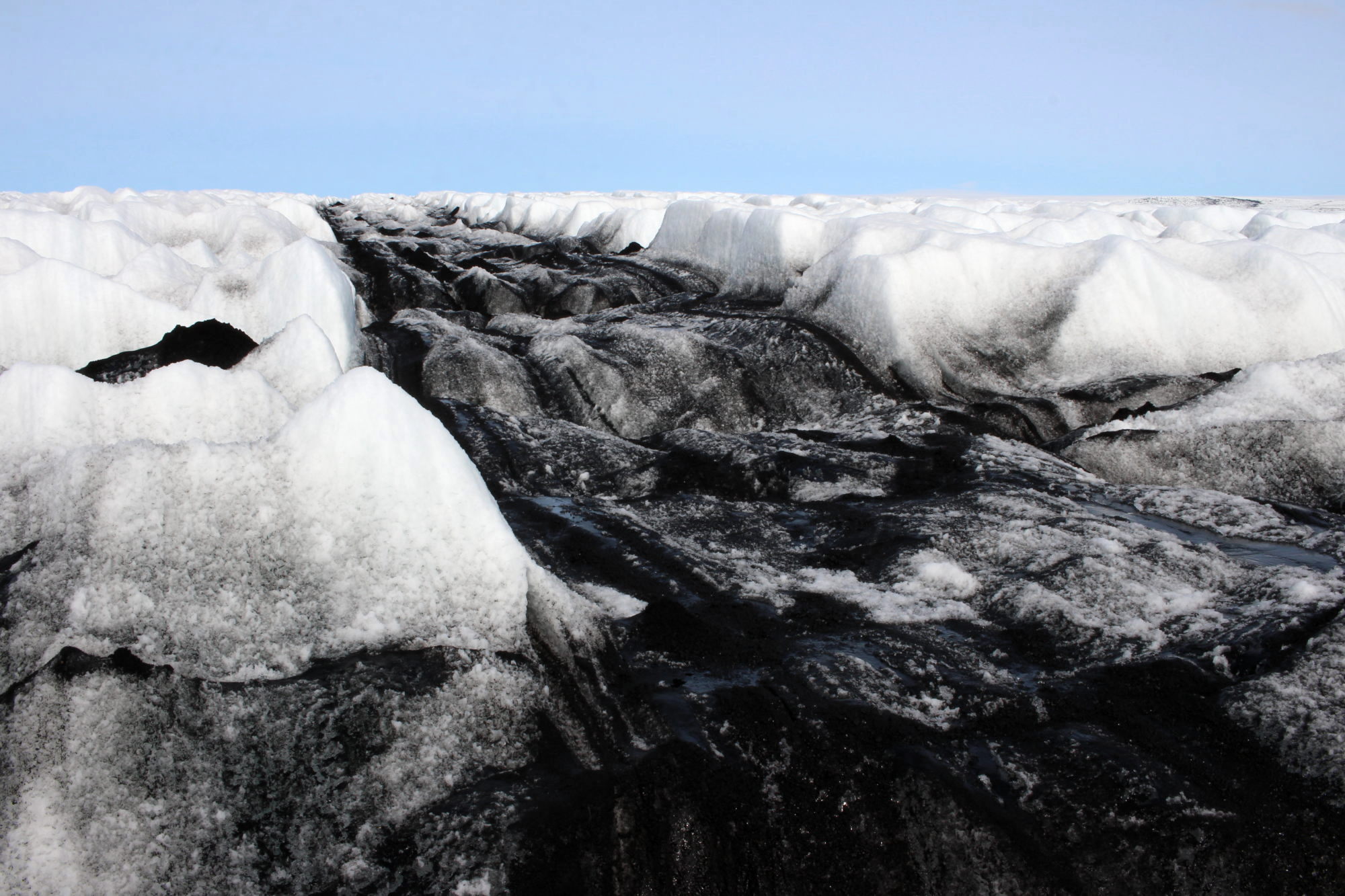

Luckily, not long after, the heavily crevassed section would give way to a friendlier terrain again interspersed with black heaps of ash hiding plain ice. In such areas of friendly small crevasses we soon realise it’s a good idea to actually look for and then follow them. Friendly crevasses are the quickest way to travel since, obviously, where there’s a crevasse you can’t have a bump. Even better than friendly crevasses are ash streets though, like flat black highways. For the first time we enjoy ourselves enough to admire the glorious play of colours surrounding us: black and white fighting for dominance, embraced from lakes of turquoise and deep blue. Water is running everywhere beneath our feet, purling out of sight into pitch black glacier mills. Having survived about half of the flight distance over the glacier, Conni naively thinks with a sigh of relief that the worst bits of this unfriendly landscape might now lie behind us. Good joke!

So far we roughly stuck to the GPS track corresponding to the path on the Sékort 5 map. The path made sense to us since it would stay away from vast orange “danger zones” directly to the West and South of Grænalón on the western side of the glacier. It would lead us through an area where the indicated danger zone is comparably narrow and therefore seemed to be a wise choice. For comparison, the 2006 GPS track from Dieter Graser went far more south. In a quickly changing environment such as a glacier, any kind of track should be used with caution. Although we contacted the Icelandic Mountain Guides, Dieter Graser and David Abadie for general information on the glacier traverse, we weren’t quite prepared for the actual danger zones of this glacier.

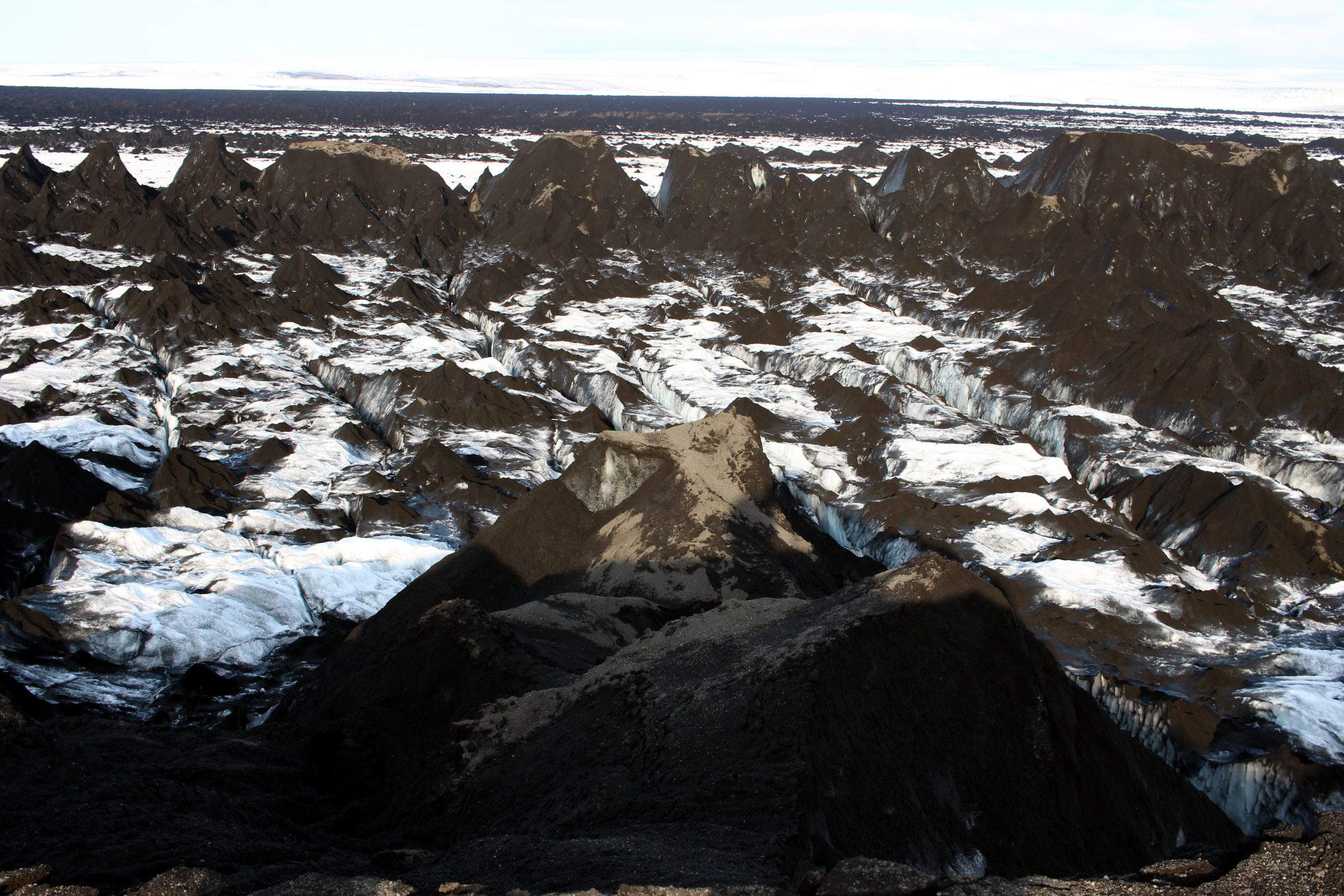

Closer and closer now come the peaks of an area the locals call “the Black Forest”. Within the distance of a few metres the surroundings change from friendly flat ice to a moonscape with huge gaping crevasses between ash-covered ice pyramids. The long line of black mountains stretches many kilometres in North-South direction, further than we can see from here. We feel slightly sick.

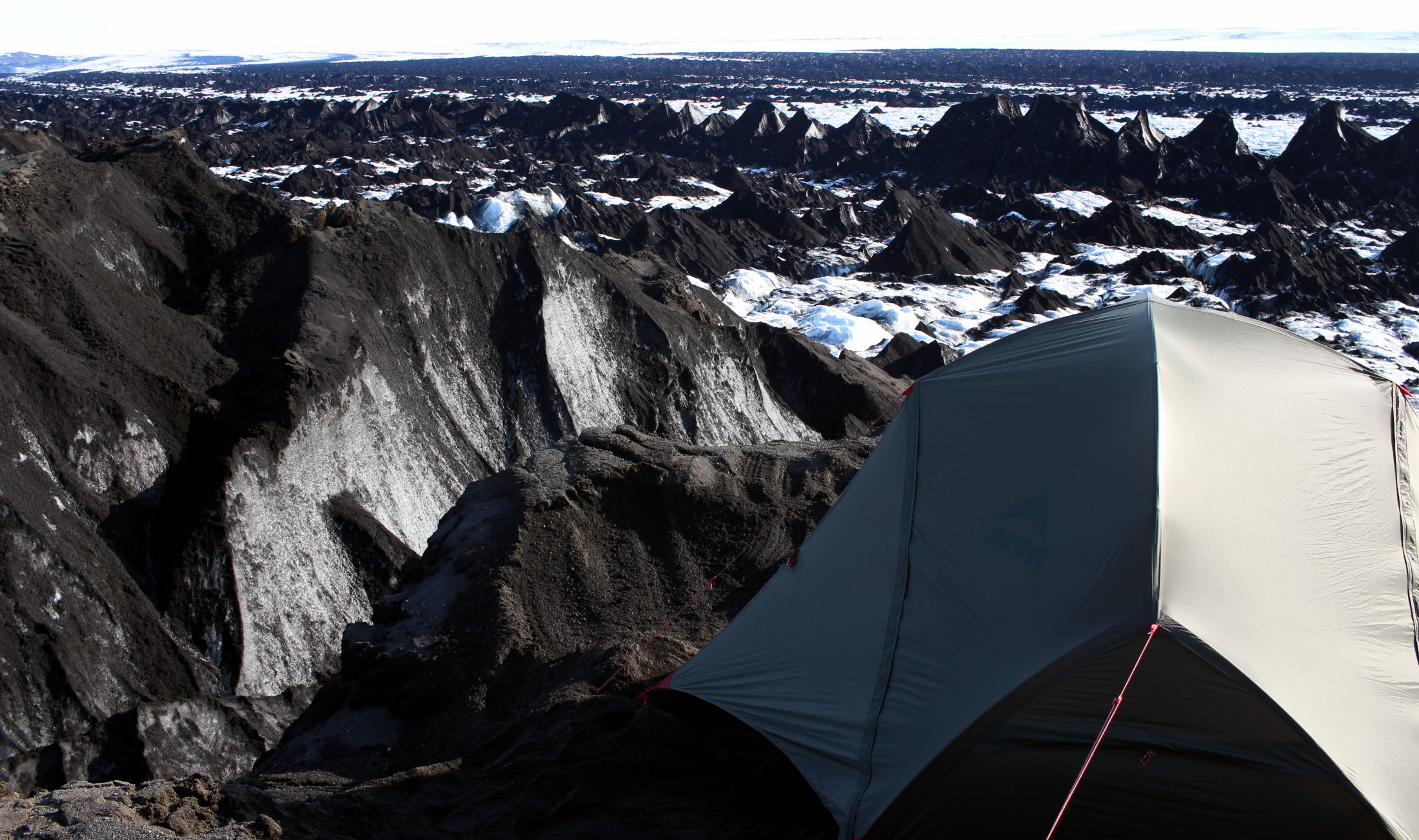

We decide to head straight into the forest to get an idea of what we’re dealing with. We find a pass that allows us to climb up the ash mountain range and Fabien is the first to have a look. His heart is sinking. The view from the top couldn’t be more intimidating. There are at least two more mountain ranges in our way with pyramids of the size of one-family houses. The flat sections between here and the second row of pyramids looks like a massacre of sliced bread; huge crevasses criss-crossing, opening their mouths between steep mountain slopes. At this point Fabien has a slight emotional breakdown, swearing and slowly realising that we won’t leave this glacier today.

In two more attempts we cross the first line of mountains, searching for a passage over the second line but we repeatedly find ourselves stuck in a labyrinth of impassable crevasses and walls of ice. Fabien always makes sure we have the exact waypoints for a retreat - without a GPS, no chance in this terrain. But what are the odds of finding a direct passage over not only one of these obstacles but over all three of them? We feel despair welling up. Of course we’re not in immediate danger as long as we don’t jump into any of these crevasses but our entire tour is at stake. Will we have to turn around? It’s late in the afternoon, we’re tired. The hostility of our surroundings is almost tangible, sucking out our energy, devouring any positivity left.

As we climb another particularly wide pyramid on the second range of ice mountains we’re discussing the options of trying our luck further to the North or South. But the ranges are long and stay high as far as we can see. We’re doubtful and on top of that we need to find a place to sleep. Fabien complains about how cold a night on the ice will be when Conni bursts out “Why can’t we stay here then? It’s warmer and soft, looks comfortable!” – we’re standing on a flat bit directly on the peak of one of the ice giants with at least 1m of sand and ash piled on top. It’s the kind of material in which no herring would hold but with some help of hiking poles buried in the ash we manage to reasonably pitch our tent. And that’s how we found ourselves sleeping cosily in the most unlikely environment one could imagine. “I think I want to go back tomorrow” says Fabien before dozing off and Conni silently agrees.