Lesson: more tools for statistical and climatological analysis#

Last week we learned how to open a NetCDF file (a data format which is very common in climate applications), select variables, do simple statistics on them, and plot them. Today we are going to introduce some more data-crunching tools and we are going to learn how to make our plots more precise and informative.

Temperature data#

Let’s open the ERA5 2m air temperature file again (ERA5_LowRes_Monthly_t2m.nc). As usual, the files for today’s class are available from the download instructions page.

# Import the tools we are going to need today:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # plotting library

import numpy as np # numerical library

import xarray as xr # netCDF library

import cartopy # Map projections libary

import cartopy.crs as ccrs # Projections list

# Some defaults:

plt.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = (12, 5) # Default plot size

ds = xr.open_dataset('../data/ERA5_LowRes_Monthly_t2m.nc')

ds

<xarray.Dataset> Size: 255MB

Dimensions: (time: 552, latitude: 241, longitude: 480)

Coordinates:

* time (time) datetime64[ns] 4kB 1979-01-01 1979-02-01 ... 2024-12-01

* latitude (latitude) float64 2kB 90.0 89.25 88.5 ... -88.5 -89.25 -90.0

* longitude (longitude) float64 4kB -179.6 -178.9 -178.1 ... 178.9 179.6

Data variables:

t2m (time, latitude, longitude) float32 255MB ...

Attributes:

Conventions: CF-1.7

institution: European Centre for Medium-Range Weather ForecastsMore control on plots#

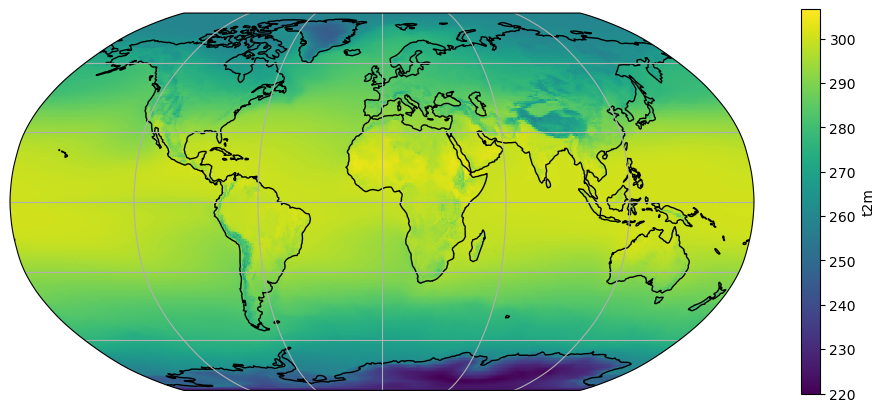

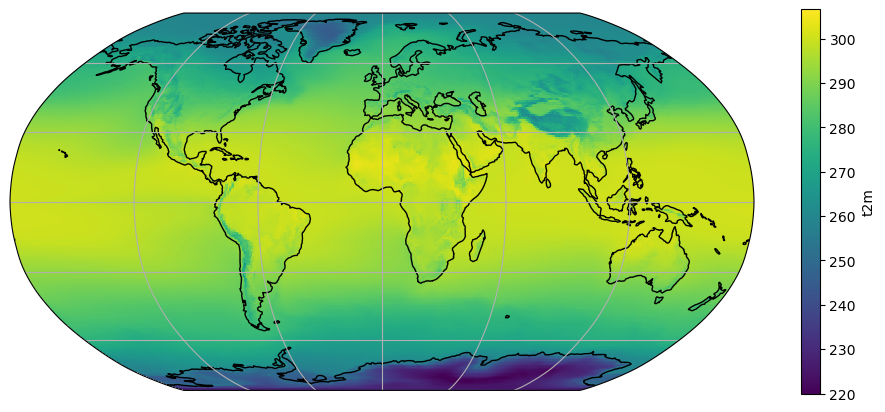

Let’s compute the time average of the air temperature:

t2_tavg = ds.t2m.mean(dim='time')

ax = plt.axes(projection=ccrs.Robinson())

t2_tavg.plot(ax=ax, transform=ccrs.PlateCarree())

ax.coastlines(); ax.gridlines();

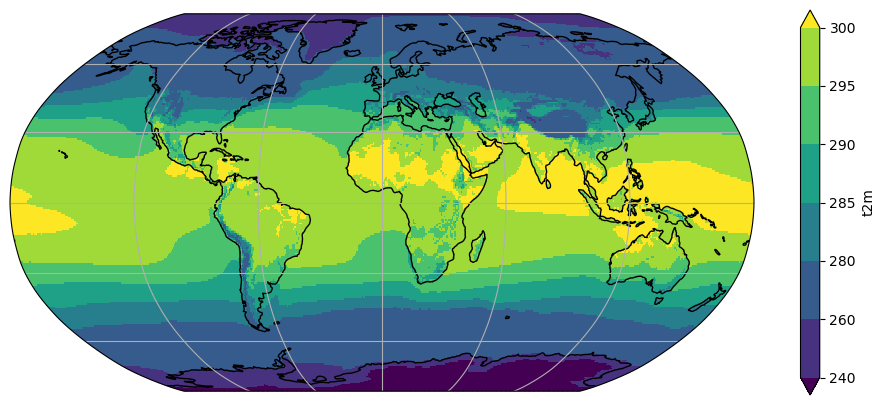

Discrete levels#

Smooth (continuous) color tables like the above “look nice”, but the human eye is not trained to see such small differences in color. For example, it would be quite difficult to tell the temperature of the Peruvian coast (above 280K? or below?). Sometimes, discrete levels are the way to go:

ax = plt.axes(projection=ccrs.Robinson())

t2_tavg.plot(ax=ax, transform=ccrs.PlateCarree(), levels=[240, 260, 280, 285, 290, 295, 300])

ax.coastlines(); ax.gridlines();

Q: What is the use of the unevenly spaced levels we set? In which range can we place the temperature off the Peruvian coast? If your eyes still can´t make out the difference, how can we be sure?

# your answer here

E: Make a new plot, but this time set levels=12.

# your answer here

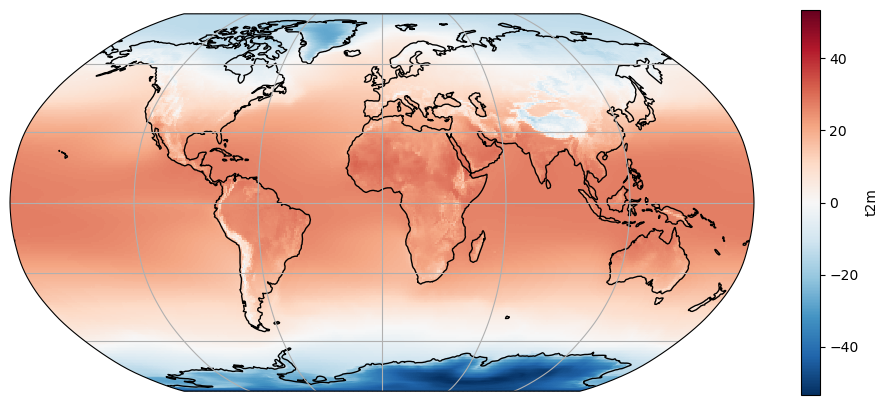

Color tables#

Let’s make a new variable called t2c_tavg, which is t2_tavg converted to degrees celsius:

t2c_tavg = t2_tavg - 273.15

ax = plt.axes(projection=ccrs.Robinson())

t2c_tavg.plot(ax=ax, transform=ccrs.PlateCarree())

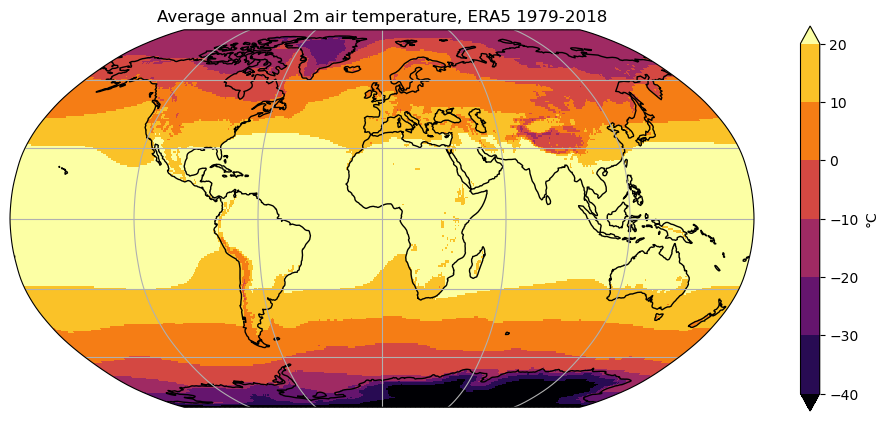

ax.coastlines(); ax.gridlines();

What happened to our plot? Note the location of the 0 on the colorbar and the automated choice of a new colorscale. Note also that the data range is mostly dictated by very cold temperatures in Antarctica. These automated choices are not always meaningful. Let’s play around a little bit:

ax = plt.axes(projection=ccrs.Robinson())

t2c_tavg.plot(ax=ax, # Role of keyword:

transform=ccrs.PlateCarree(), # Role of keyword:

cmap='inferno', # Role of keyword:

center=False, # Role of keyword:

vmin=-40, # Role of keyword:

vmax=20, # Role of keyword:

levels=7, # Role of keyword:

cbar_kwargs={'label': '°C'} # Role of keyword:

)

ax.set_title('Average annual 2m air temperature, ERA5 1979-2018')

ax.coastlines(); ax.gridlines();

Q: try to understand the role of each keyword by trying to use each of them separately. If you’re still unsure, a look at xarray’s documentation might be helpful. Add some notes to the inline code comments above to help you remember.

Note: a list of matplotlib’s color tables can be found here.

# your playground here

Slightly faster map plots#

xarray’s .plot method internally uses matplotlib’s pcolormesh which, for reasons too long to explain here, is the more accurate way to represent gridded data on a map. If you are willing to sacrifice some accuracy (not visible with the bare eye at the global scale), you can also use imshow:

t2_tavg = ds.t2m.mean(dim='time')

ax = plt.axes(projection=ccrs.Robinson())

t2_tavg.plot.imshow(ax=ax, transform=ccrs.PlateCarree())

ax.coastlines(); ax.gridlines();

This plot should render 3 to 4 times faster than the default plot, which is useful for data exploration. It should not be used for final rendering or for regional plots, though.

Working with time series#

The selection tools we learned about last week also apply to time series. They are quite clever and very flexible:

t2 = ds.t2m

t2.sel(time='2008')

<xarray.DataArray 't2m' (time: 12, latitude: 241, longitude: 480)> Size: 6MB

array([[[246.4758 , 246.4758 , ..., 246.4758 , 246.4758 ],

[248.12814, 248.12228, ..., 248.12424, 248.12619],

...,

[242.43283, 242.45041, ..., 242.39767, 242.4172 ],

[242.79416, 242.79416, ..., 242.79416, 242.79416]],

[[249.47383, 249.47383, ..., 249.47383, 249.47383],

[250.00703, 249.99336, ..., 250.0207 , 250.01485],

...,

[233.04805, 233.06563, ..., 233.00508, 233.02852],

[233.77461, 233.77461, ..., 233.77461, 233.77461]],

...,

[[255.86382, 255.86382, ..., 255.86382, 255.86382],

[256.39508, 256.38727, ..., 256.40485, 256.40094],

...,

[235.71538, 235.7271 , ..., 235.68413, 235.69975],

[236.43803, 236.43803, ..., 236.43803, 236.43803]],

[[251.50368, 251.50368, ..., 251.50368, 251.50368],

[252.31813, 252.31422, ..., 252.32594, 252.32204],

...,

[245.15211, 245.16383, ..., 245.12672, 245.1404 ],

[246.6072 , 246.6072 , ..., 246.6072 , 246.6072 ]]], dtype=float32)

Coordinates:

* time (time) datetime64[ns] 96B 2008-01-01 2008-02-01 ... 2008-12-01

* latitude (latitude) float64 2kB 90.0 89.25 88.5 ... -88.5 -89.25 -90.0

* longitude (longitude) float64 4kB -179.6 -178.9 -178.1 ... 178.9 179.6

Attributes:

long_name: 2 metre temperature

units: K

standard_name: unknownQ: what did we just do? Does that make sense to you? Try to understand the output of the following commands:

t2.sel(time=’2008-02’)

t2.sel(time=’2008/02’)

t2.sel(time=slice(‘2008’, ‘2012’))

# Your answer here

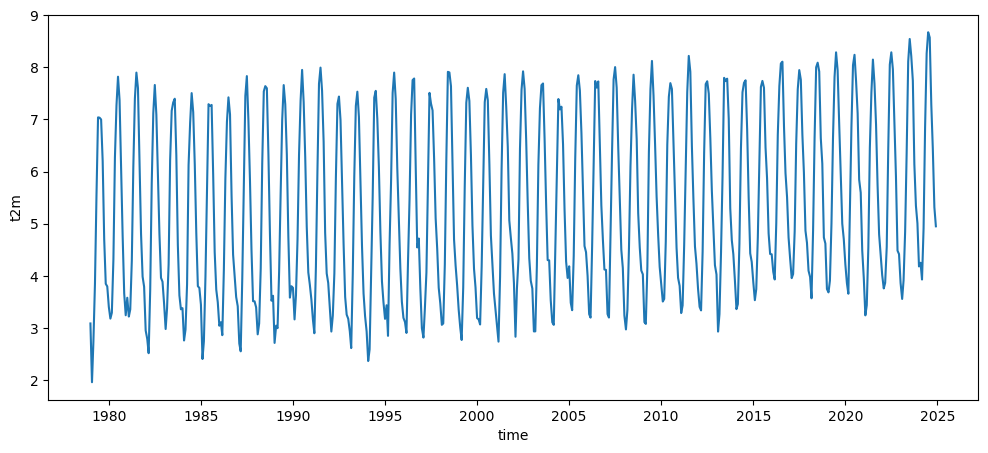

Time series of globally averaged fields#

If you remember last week, you should understand well what the following command will do:

ts_t2_c = t2.mean(dim=['longitude', 'latitude']) - 273.15 # convert into Celsius

ts_t2_c.plot();

Logically, the global average temperature on Earth would be:

ts_t2_c.mean(dim='time')

<xarray.DataArray 't2m' ()> Size: 4B array(5.285408, dtype=float32)

But… wait? This is way colder than expected! (Q: do you remember what is the average air temperature at the Earth surface?). Indeed, we forgot to take the latitudinal effect into account. If you forgot about how to do that already, go back to last week’s lesson.

# Meridional weights

weight = np.cos(np.deg2rad(ds.latitude))

weight = weight / weight.sum()

# Meridionally weighted zonal mean

zonal_mean_t2_c = t2.mean(dim='longitude') - 273.15 # convert into Celsius

weighted_zonal_mean_t2_c = zonal_mean_t2_c * weight

weighted_ts_t2_c = weighted_zonal_mean_t2_c.sum(dim='latitude')

Now, in comparison to last week, the second line (zonal_mean_t2_c * weight) did even a little bit more of magic. Although zonal_mean_t2_c is of dimensions (time, latitude), we could multiply it by an array of dimension latitude. This is called “broadcasting” in the numpy jargon, and something you don’t have to worry about in this lecture: xarray does it for you! Indeed, xarray knows about the dimensions of your data (and their coordinates) and will always make arithmetic operations match these.

E: make a plot of this time series and compute its average. Does the global average now fit better to what we said in the lecture?

# your answer here

Note that the operations above were only valid because averaging is a linear operation, i.e. commutative. For any field \(A\), the equality \(\left[ \overline{A} \right] = \overline{\left[A \right]}\) is always true.

Resample time series data#

Resampling is the operation of changing the sampling of the data, i.e. the frequency at which it is sampled. One of the most meaningful ways to resample is to do an average, for example over the year:

tsa_t2_c = weighted_ts_t2_c.resample(time='YS').mean()

E: check that tsa_t2_c is what you think it is. What could 'YS' mean? Try 'YE' for a change, and note the difference.

Note that averaging is not the only way available to resample data. Try .std() and .max(), too.

# your answer here

E: describe the features of the yearly average plot. Does it surprise you, or is it the way you thought it would be? Compute the standard deviation of this time series (tip: .std())

# your answer here

Compute the monthly climatographies (or annual cycle)#

Another way to look at time series data is to average them according to the time of year to study the annual cycle. This is done with the .groupby() method:

tsm_t2_c = weighted_ts_t2_c.groupby('time.month').mean()

E: check that tsm_t2_c is what you think it is. What is the new dimension of the data? Plot it. Can you explain what you see? Why does the global Earth temperature have an annual cycle?

# your answer here

E: select the month of August out of tsm_t2_c and print its value. Compare it to the annual average. Tip: selection happens over a dimension that must be named. What is the dimension over which we need to select, in the tsm_t2_c file?

# Your answer here

Averages and anomalies#

A very common way to decompose time-series is to normalize them. Let \(A\) be any field, function of time \(t\). Then:

Where \(A'\) is called the fluctuating component of \(A\), \(A'(t)\) being the anomaly of \(A\) at the time \(t\). Often the variable t is omitted from the notation, i.e. one writes \(A = \overline{A} + A'\)

E: compute the global temperature anomaly for the year 2024 with respect to the 1979-2024 average. Tip: Use the tsa_t2_c timeseries for this.

# your answer here

E: now compute the global temperature anomaly for the year 2024 with respect to the 1979-1999 average. Tip: the code is very similar to the above! However you will need to apply .sel with a slice= before computing the average.

# Your answer here

E: by noting that the functions applied to 1d data above also apply to 3d data, compute the temperature anomaly for the month of January 2010 with respect to the 1979-2024 January average. Tip: here are the required steps:

Create a variable

jan2010_t2mby selecting the month of January 2010 out ofds.t2mNow create a

monthly_t2mvariable by applyinggroupbytods.t2mSelect the month of January out of

monthly_t2m-> the is the the 1979-2024 January average!Substract this value from

jan2010_t2m

# your answer here

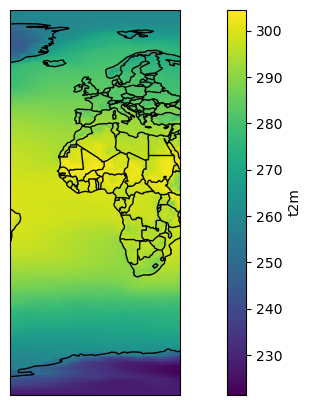

Selecting specific areas of our data#

As for the time above, one can select slices out of the data:

t2_reg = t2_tavg.sel(longitude=slice(-40, 40))

ax = plt.axes(projection=ccrs.PlateCarree()) # Note that I changed the projection

t2_reg.plot(ax=ax, transform=ccrs.PlateCarree())

ax.add_feature(cartopy.feature.BORDERS); # What does this command do?

ax.coastlines();

E: create a new “t2c_reg” variable which is a subset of t2c_tavg between the longitudes (-20, 60) and the latitudes (40, -40). Plot the result. (hint: yes, I wrote (40, -40) and not (-40, 40))

# your answer here

Selection based on a condition#

What if we are interested into air temperature on land only, and want to remove the oceans from our analyses? For this we are going to have to “mask out” the oceans grid points. First, we will need to open the “invariant: file:

nc_inv = xr.open_dataset('../data/ERA5_LowRes_Invariant.nc')

nc_inv

<xarray.Dataset> Size: 931kB

Dimensions: (latitude: 241, longitude: 480)

Coordinates:

* latitude (latitude) float64 2kB 90.0 89.25 88.5 ... -88.5 -89.25 -90.0

* longitude (longitude) float64 4kB -179.6 -178.9 -178.1 ... 178.9 179.6

Data variables:

lsm (latitude, longitude) float32 463kB ...

orography (latitude, longitude) float32 463kB ...

Attributes:

Conventions: CF-1.7

institution: European Centre for Medium-Range Weather ForecastsE: explore this new data file (variables, units). Plot the variables.

# your answer here

OK, so in the lsm variable “1” is land, “0” is ocean. We are going to use this information to mask out the values from the ocean:

masked_t2_avg = t2c_tavg.where(nc_inv.lsm > 0.5)

E: Plot this new variable on a map.

# your answer here

What’s next?#

You are now ready for this week’s assignment! If you want to know more about xarray’s plotting capabilities, visit the excellent documentation.